Introduction

During an attack, lateral movement is crucial in order to achieve the operation’s objectives. Primarly, two main strategies exist that would allow an attacker to execute code or exfiltrate data from other hosts after obtaining a foothold within an environment:

- Operate from the compromised endpoint/s

- Pivot and use their tooling to access other targets

Operating from a compromised endpoint has its risks, every action you take as an attacker gives the blue team a detection opportunity (line totally stolen from Raphael Mudge from his videos).

On the other hand, pivoting from a compromised host would allow an attacker not to “pollute” the initial foothold and use their own tools. This type of approach is often referred as “bring your own tool” or BYOT.

While testing Windows-based environments, the de facto framework used to operate in accordance to the BYOT strategy is Impacket.

This post’s aim is to shed some light on the behaviours of the Impacket framework from a defensive standpoint. Probably none of this traits are suitable to a signature-based approach, however, they can be used as part of your hunting sprints.

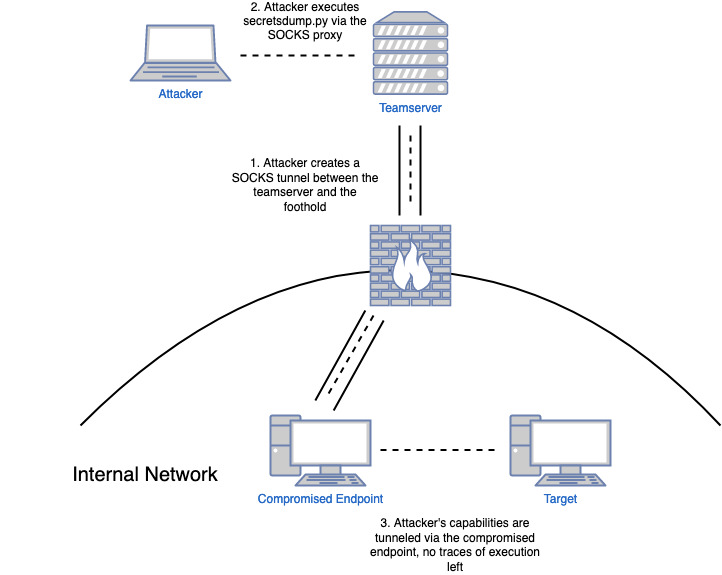

It is common during different types of engagements to proxy Impacket’s capabilities through a SOCKS proxy using tools like proxychains. The SOCKS proxy can be created using different methods, frameworks such as Metasploit or Cobaltstrike provide this functionality.

The following diagram describes an example of an attacker that pivots through a compromised workstation to reach another internal target. The technical objective in this scenario is to extract the LSA secrets and the password hashes of local users of the machine marked as “target”:

This strategy has been used by red teamers for a while now and it has been documented in different forms. Some of the references that were used to write this post:

- Dominic Chell - What I’ve Learned in Over a Decade of “Red Teaming”

- Artem Kondratenko - A Red Teamer’s guide to pivoting

- CoreSecurity - Impacket

The testing environment we are going to use to extract behaviours has Sysmon logging in place, advanced audit policies configured and the capabilities to capture and analyse network traffic. I do appreciate that this setup might not reflect your environment and sometimes the amount of logs generated using these settings might not be suitable for production. However, the aim of this post is mainly explore different tools and techniques and to do so we need a decent level of telemetry.

NOTE: I’m not going to cover every single Impacket tool, just the one that I tend to use more often during engagements.

Tools

secretsdump.py

Secretsdump is a script used to extract credentials and secrets from a system. The main use-cases for it are the following:

- Dump NTLM hash of local users (remote SAM dump)

- Extract domain credentials via DCSync

Remote SAM Dump

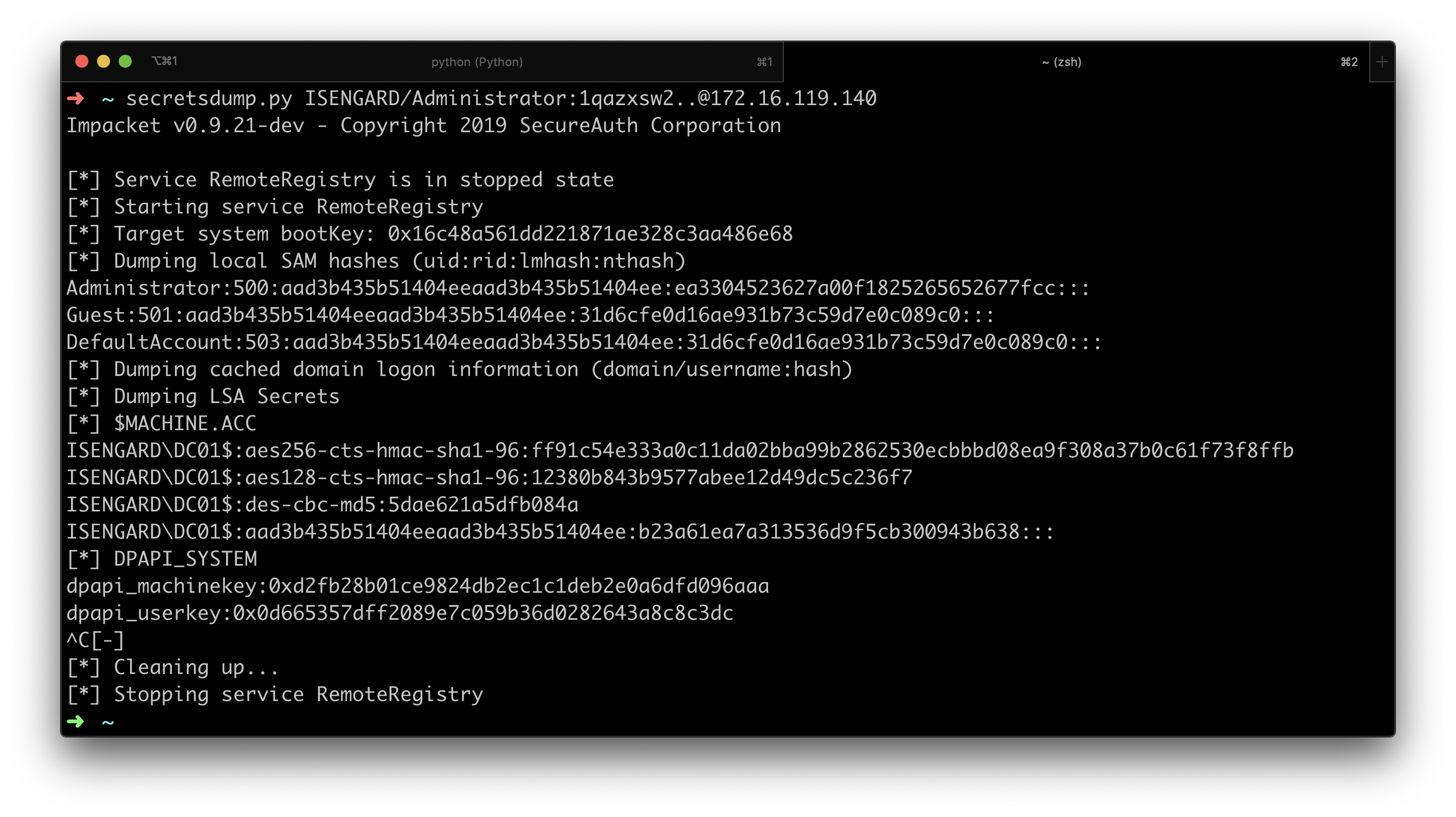

An example execution would be the following:

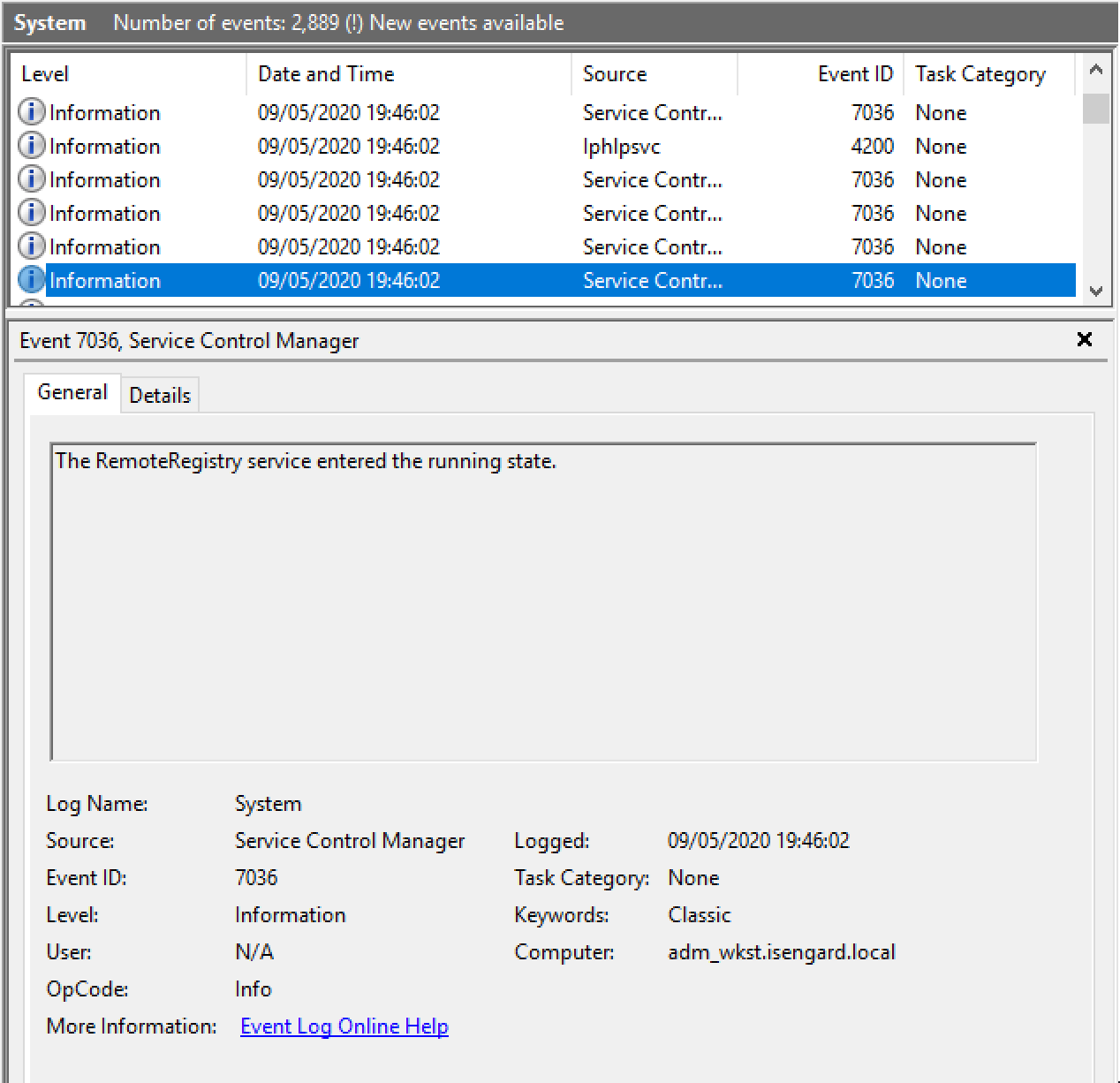

The first thing we can note here, is that before extracting credentials the tool enables the RemoteRegistry service on the remote endpoint. Since the RemoteRegistry service is in a stopped state by default, its activation might be something suspicious:

Remote registry can be used for a number of totally legit administrative tasks and therefore cannot be used on its own to determine whether it is originated from a malicious activity or not.

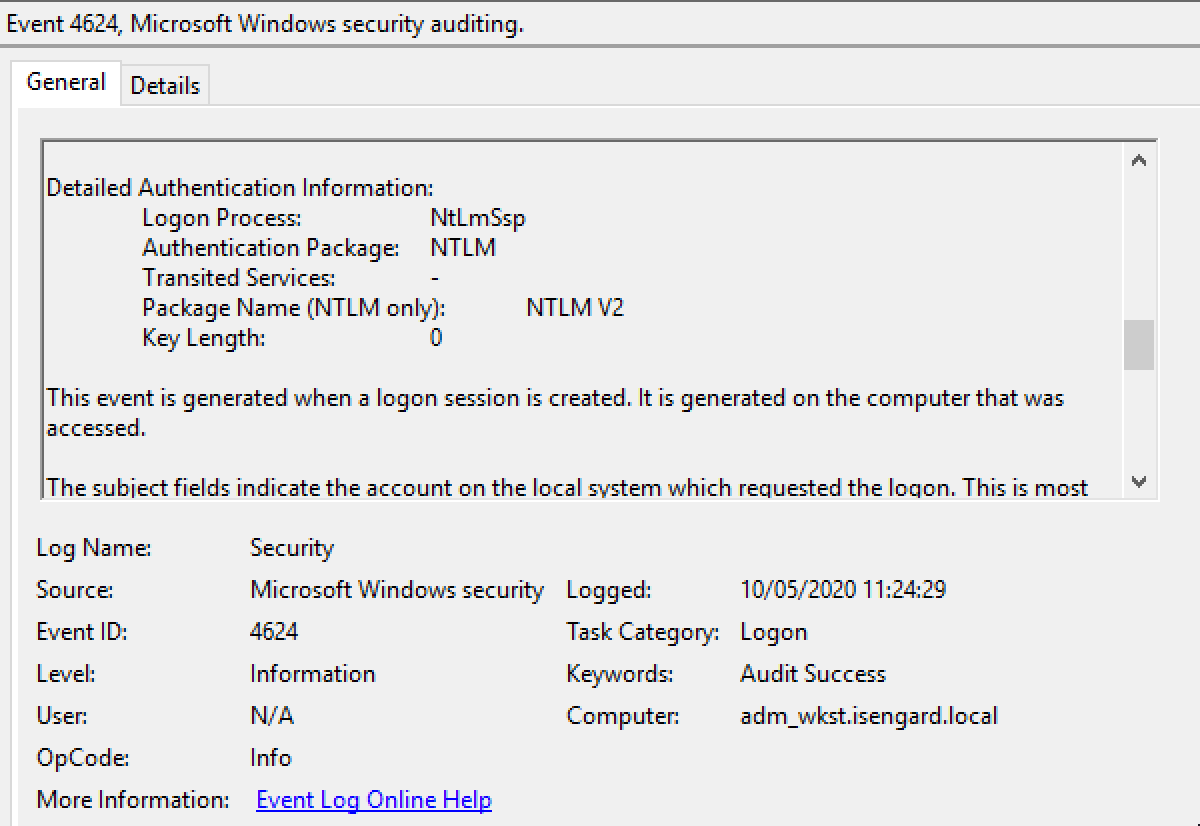

If we inspect the Security event log, we would find the following events that happened in a short time frame:

- 4624, a successful logon event. The logon type in this case would be 3 (network logon) and the authentication package would be NTLM. The “key length” parameter would also be 0.

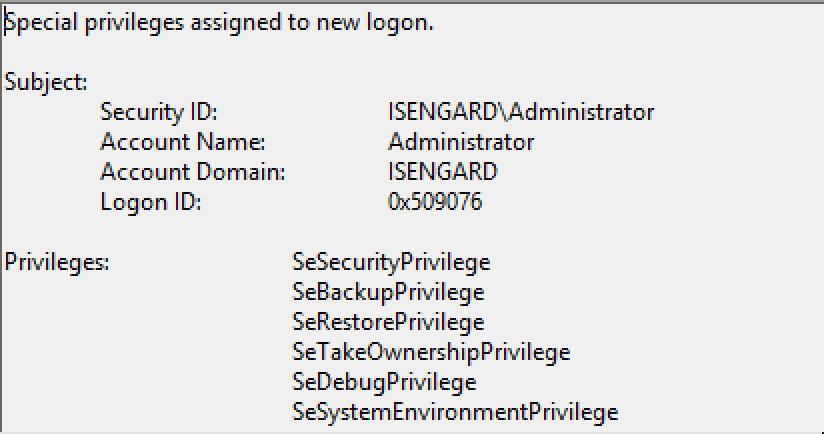

- 4672, special privileges assigned to a logon session. This event is generated when elevated privileges are assigned. If we inspect the privileges we should see something like this:

As it is possible to see, privileges such as SeDebug or SeBackup were assigned to the logon session. Although these indicators are not a silver bullet, if combined should give the analyst a good idea of what happened.

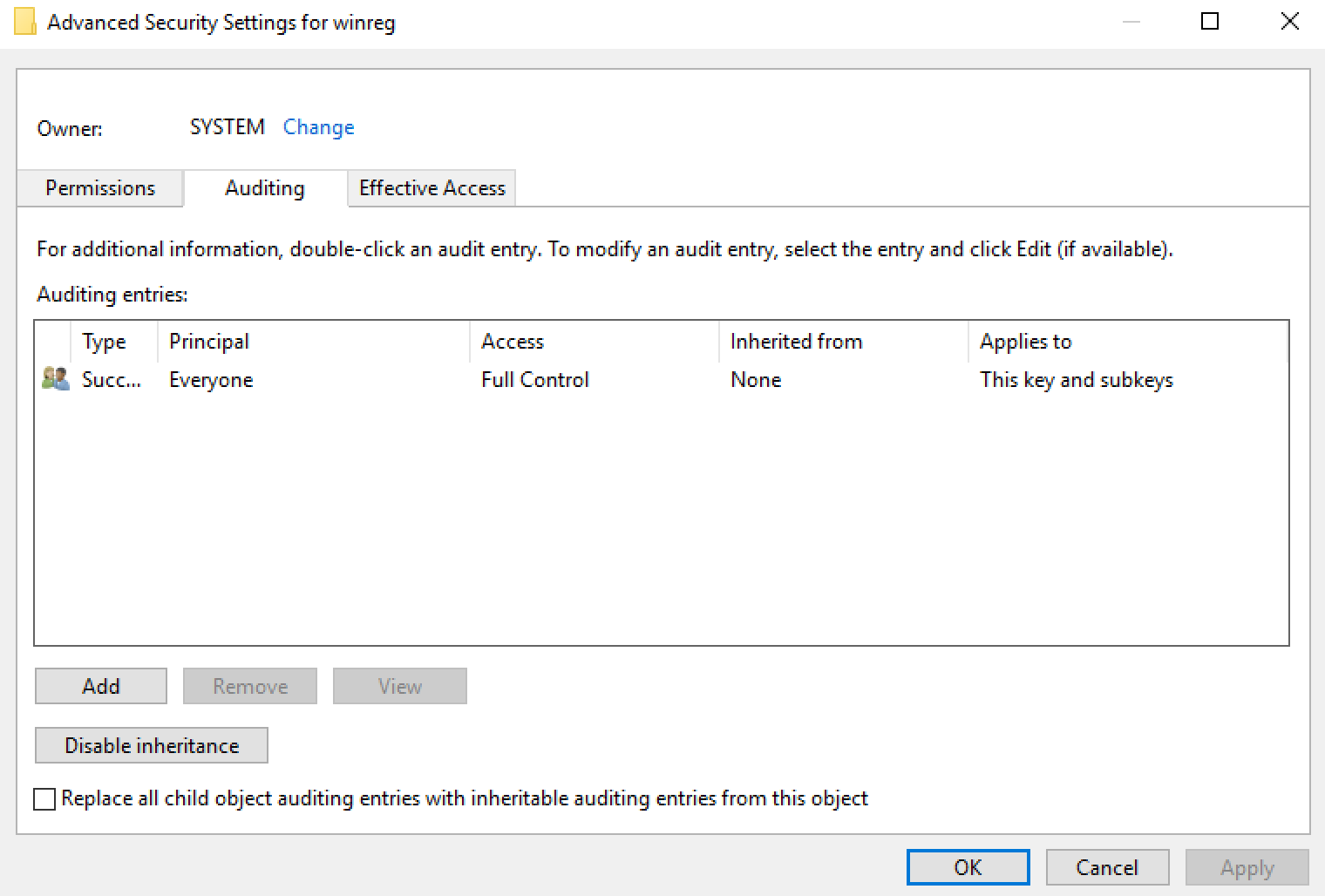

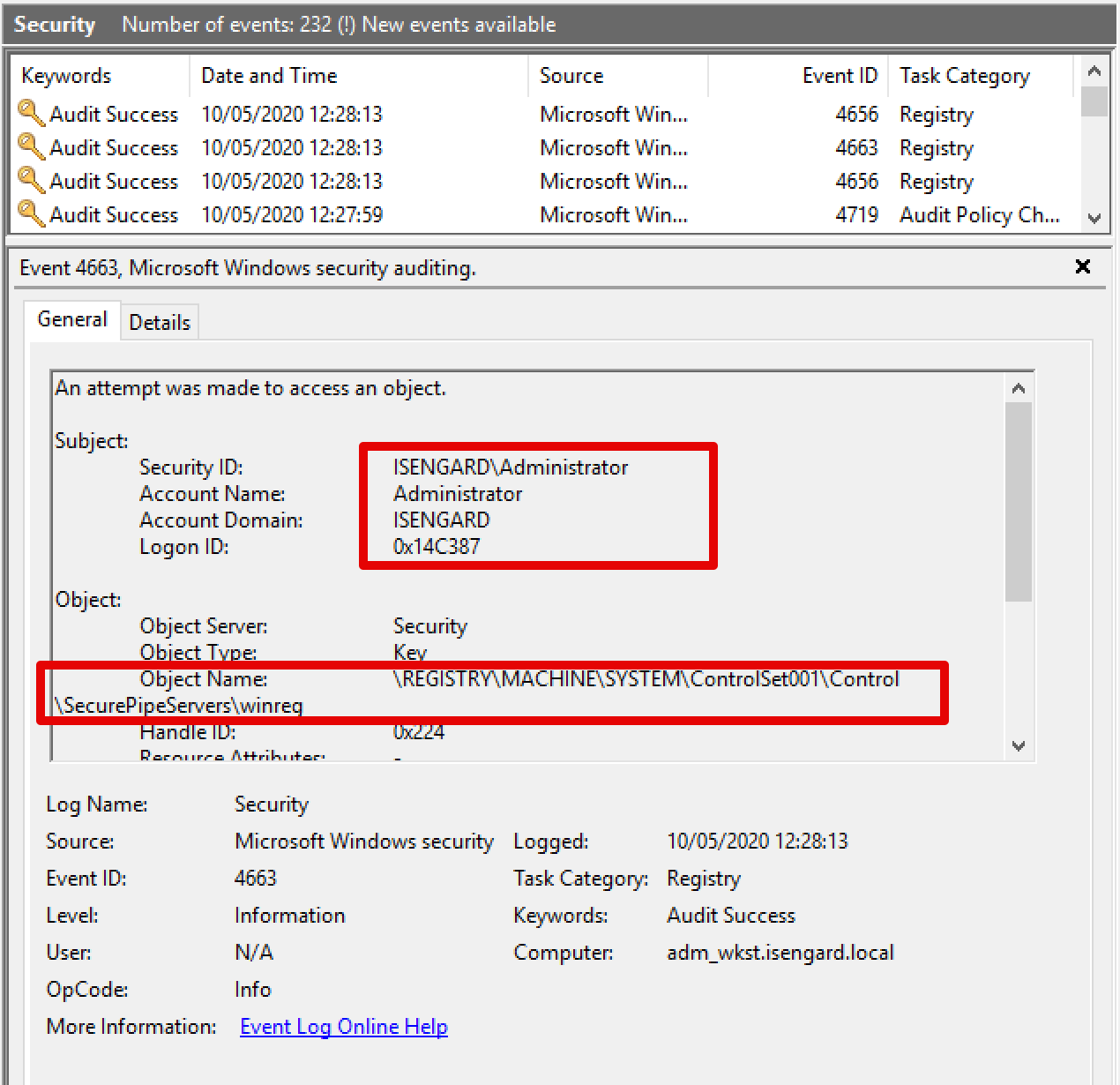

Another alternative is to configure a SACL (Security Access Control List) to the object responsible for the remote access to the registry. Microsoft explains how it is possible to change the ACL to allow other users to remotely manage the Windows registry via the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\ SecurePipeServers\winreg registry value. However, what we can do is to configure a SACL that logs every access to the aforementioned registry key as follows:

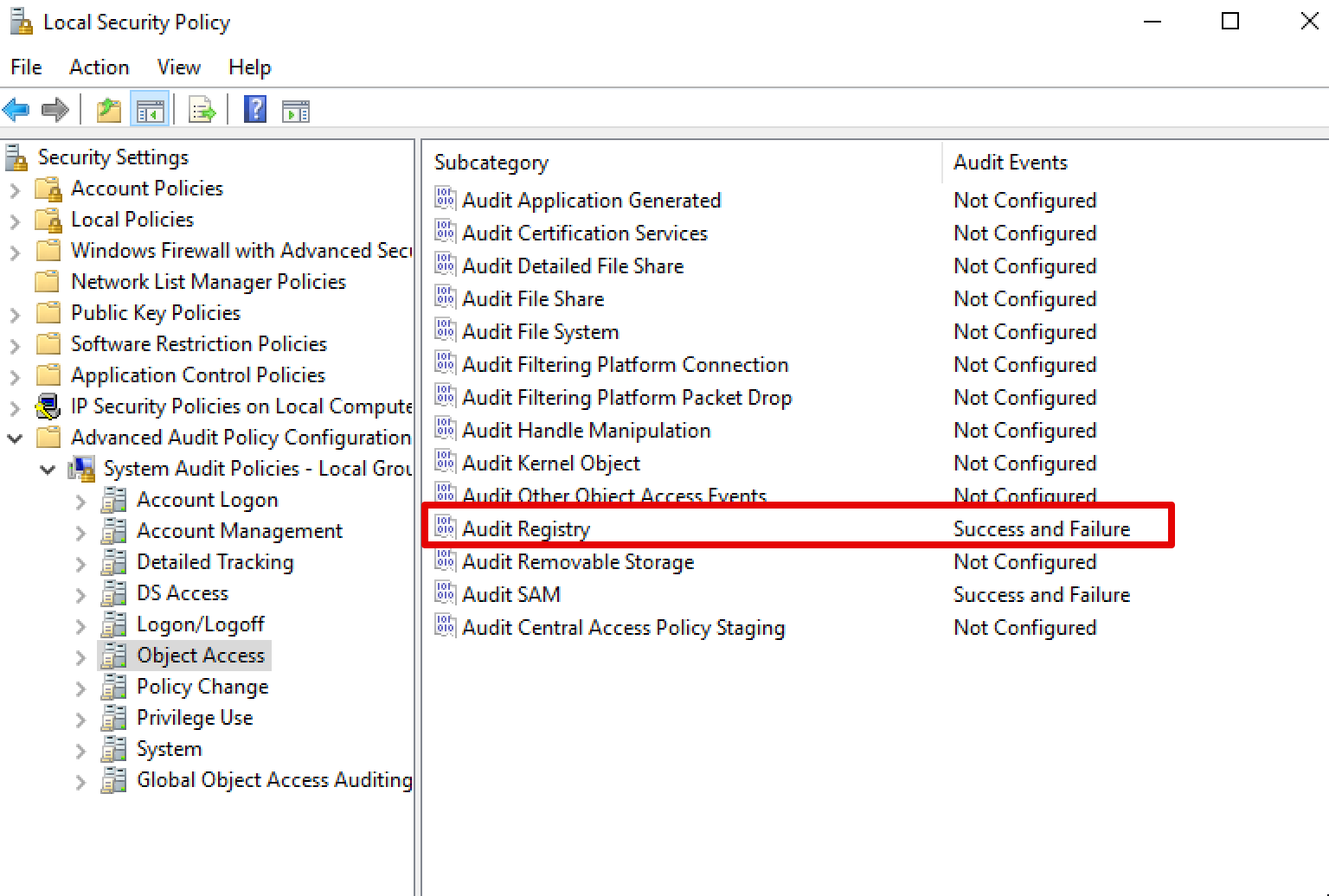

After configuring the SACL, it would be possible to configure registry access auditing within the “Advanced Audit Policy”:

If we repeat the attack using secretsdump, we will now obtain the following events:

DCSync

DCSync is a credential extraction attack that abuses the Directory Service replication protocol to gather the NTLM hash of any user within a compromised Active Directory.

Within Impacket, it is possible to perform a DCSync attack using the following command:

secretsdump.py -just-dc ISENGARD/Administrator:1qazxsw2..@172.16.119.140

I’m not going to do a deep dive on DCSync, the available information online is more than comprehensive. Additionally, DCSync performed using Impacket generated the same type of telemetry of the standard attack using Mimikatz and therefore the detections already in place should be enough.

To quickly recap, there are two main strategies for detecting DCSync:

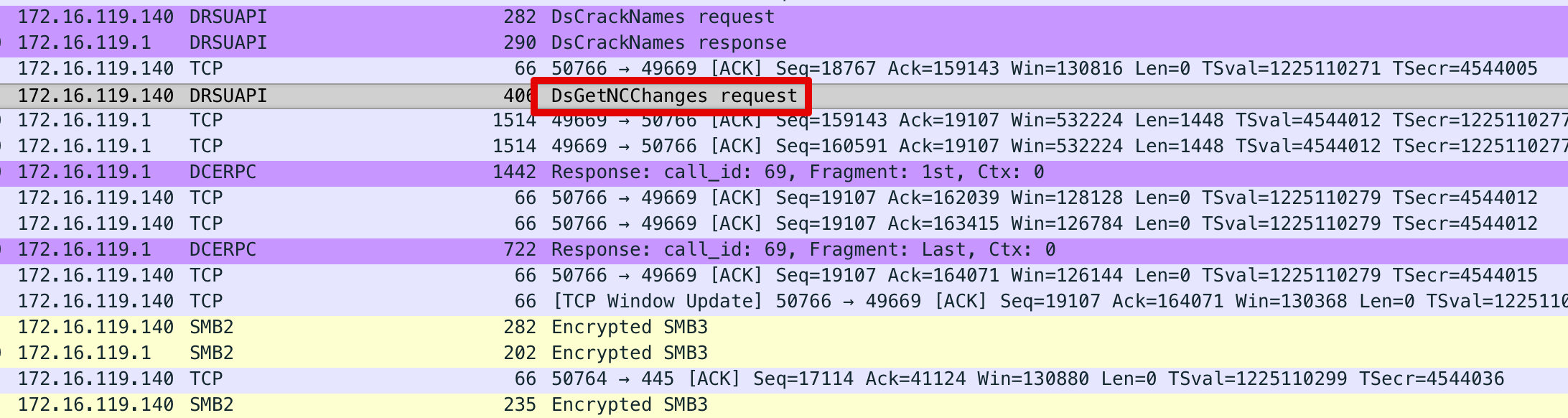

Via network traffic analysis. In fact, the RCP calls used to fetch the data from a target domain controller can be seen in “clear text” on the wire:

Despite this method is normally invoked by other domain controllers legitimately, if the same method is found to be invoked by a non-DC host it would be a good indicator of malicious activity.

By enabling object auditing on the domain object within AD. An example of a Sigma rule used to do so can be found in the Sigma original repository.

wmiexec.py

wmiexec.py is another script part of the Impacket framework. It is used to silently execute commands against a compromised endpoint using WMI.

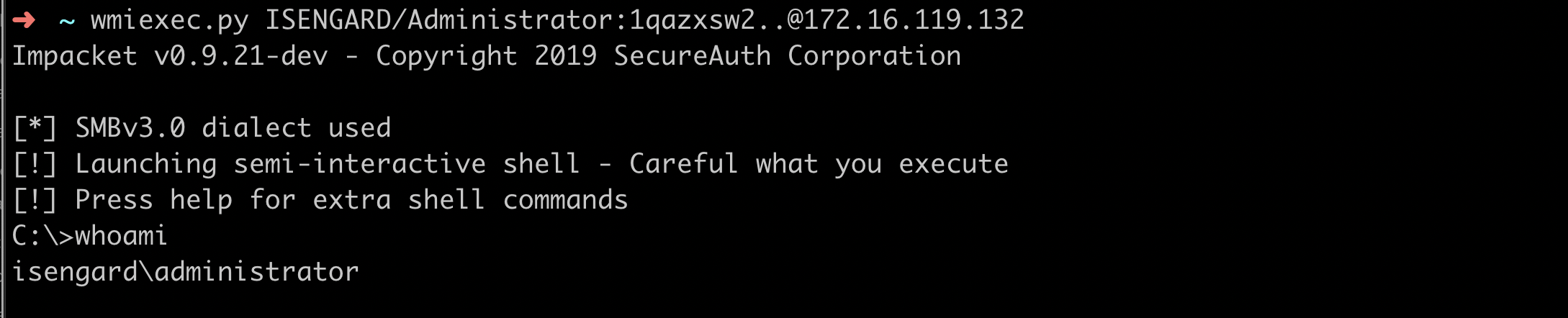

An example of execution against a test system is shown below:

It is possible to tackle this problem from two different angles. In fact, this type of technique leaves traces on both the target endpoint and within the network traffic.

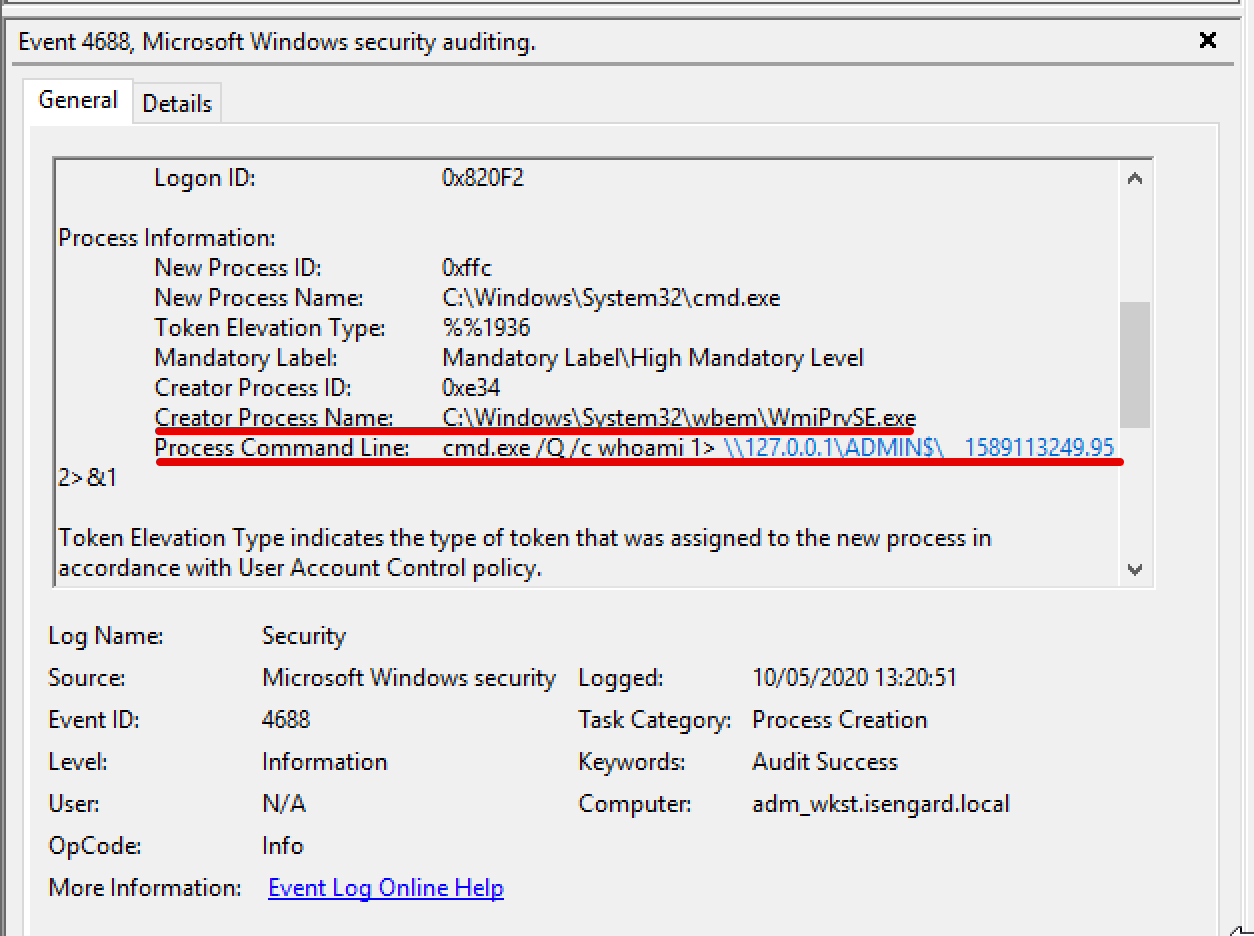

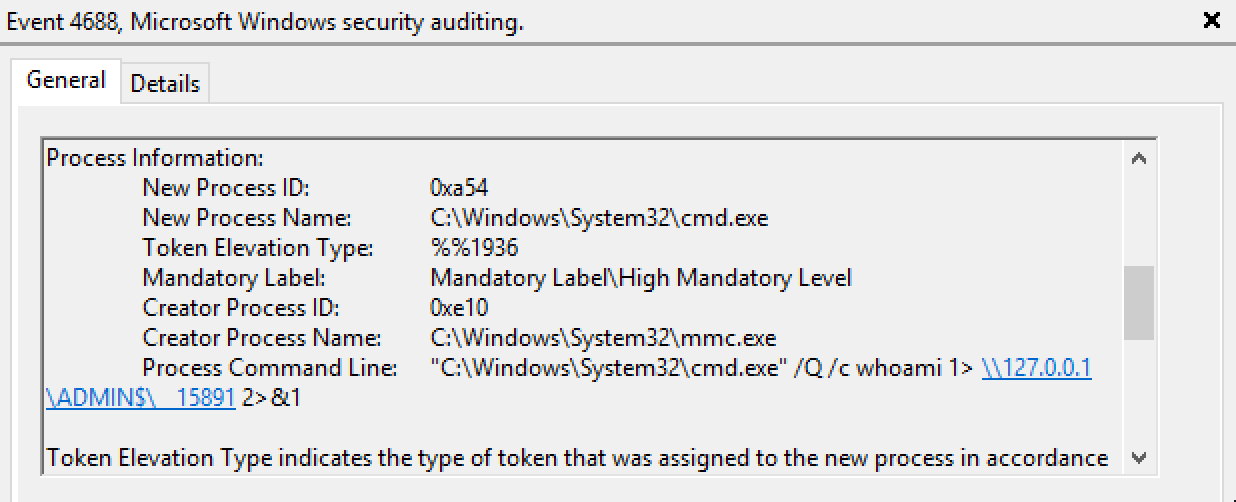

After executing the attack above, if we examine process creation events, we might spot something like the following:

As we can see, cmd.exe was spawned by WmiPrvSE.exe. This usually means that cmd.exe was spawned using WMI. However, this might be a legitimate use case in some environment and therefore not malicious per se.

If we inspect closer the command line arguments (if using the Security logs, it needs to be enabled) we might actually find that wmiexec is redirecting the output of the command we executed in a file inside \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$. We could draw the conclusion that wmiexec uses the following format as a template for executing commands:

cmd.exe /Q /c 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\ 2>&1

That’s a good starting point for hunting for this type of activities! We have two detection opportunities here: command execution using suspicious arguments and a file write event.

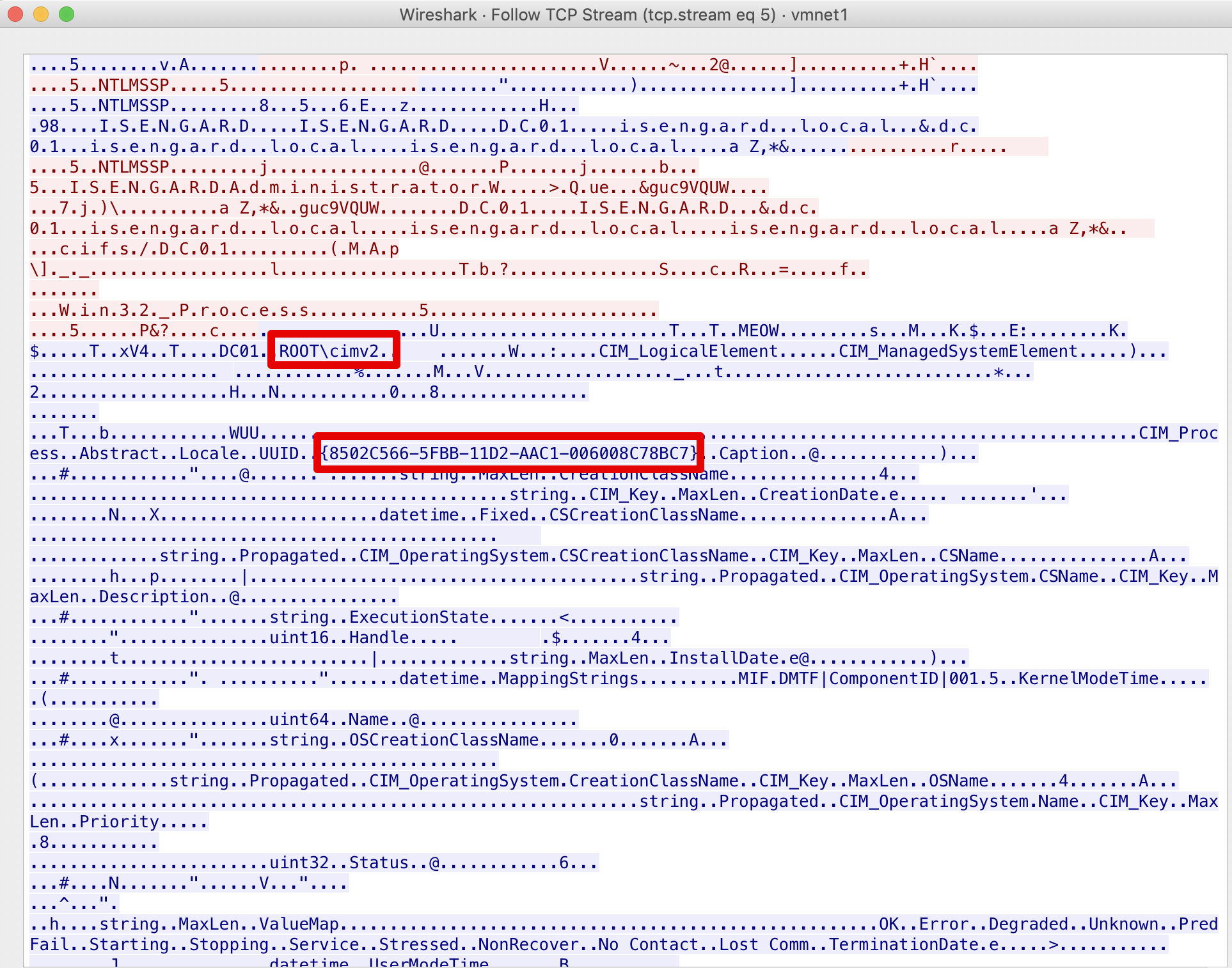

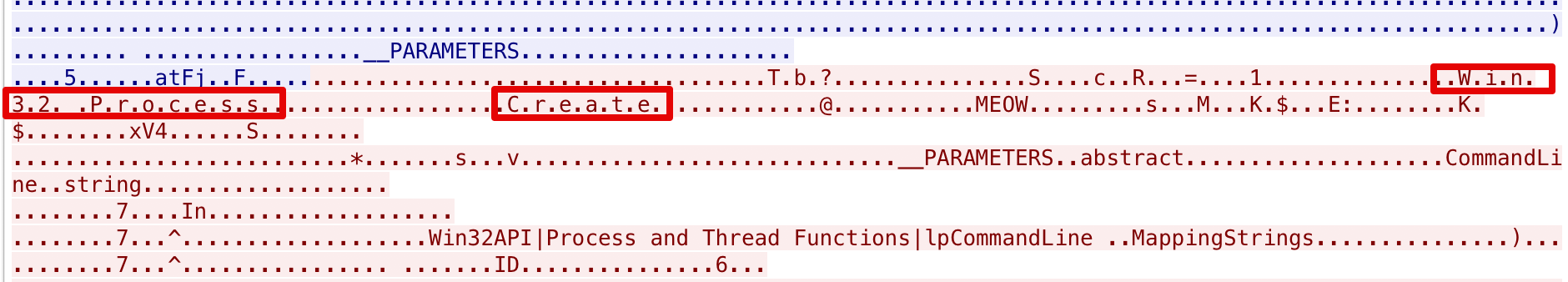

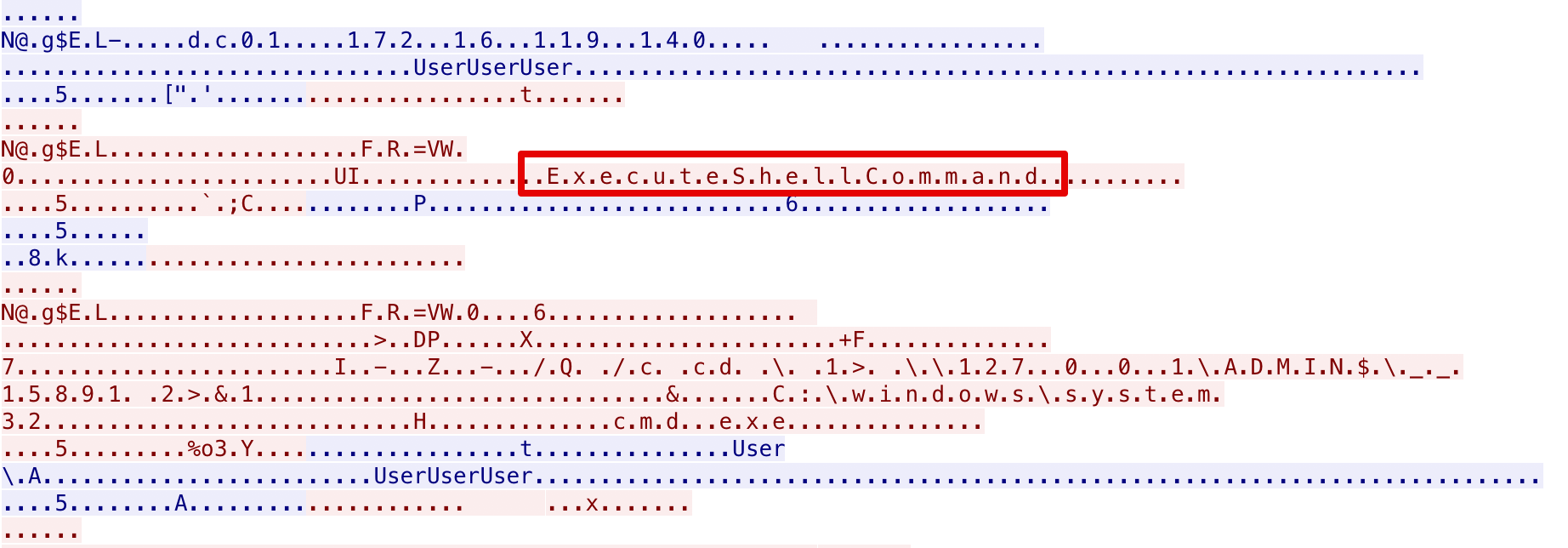

wmiexec uses DCOM to connect to a remote target, and its transport mechanism is TCP. Within a packet capture, we could find evidences of this execution by analysing the DCOM/DCERPC protocols. Byte stream is shown below:

Knowing that in order to invoke methods via DCOM interface it is needed to reference the DCOM object via its GUID or application name, we could spot in the figure above the GUID 8502C566-5FBB-11D2-AAC1-006008C78BC7. Just googling it would reveal us that it is the GUID of the CIM_Process class, responsible for process management.

Another indicator could be the Win32_ProcessStartup or Win32_Process strings in the same byte stream:

Now, using the Win32_Process is not the only class that it can be used to spawn processes, as discovered by Cybereason’s research. However, considering that at the moment we are only interested in Impacket’s specific implementation, this will be enough.

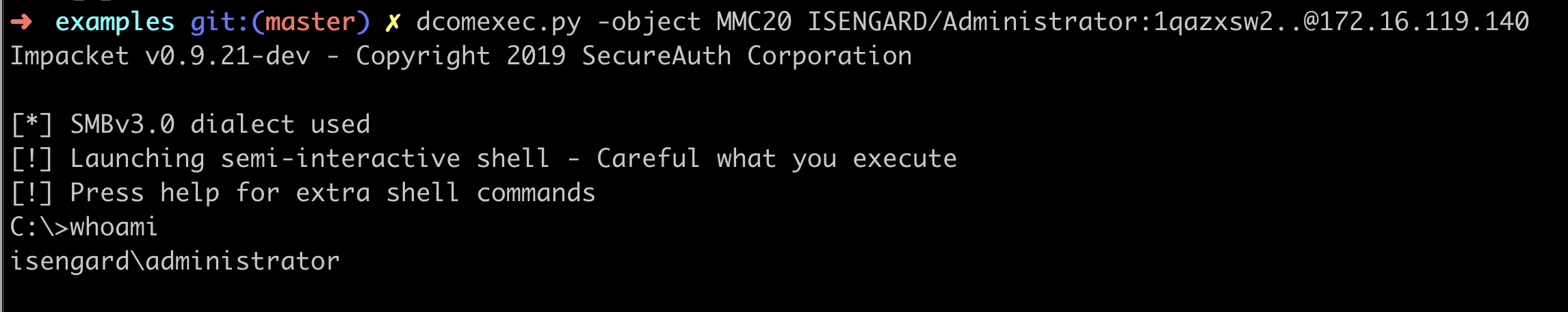

dcomexec.py

The purpose of dcomexec is similar to wmiexec, execute commands on a remote endpoint. The underlying execution method, however, is different. In fact, with dcomexec we will use specific DCOM techniques to execute commands such as:

MMC2.0ShellBrowserWindowShellWindows

The execution agains a testing system would look like this:

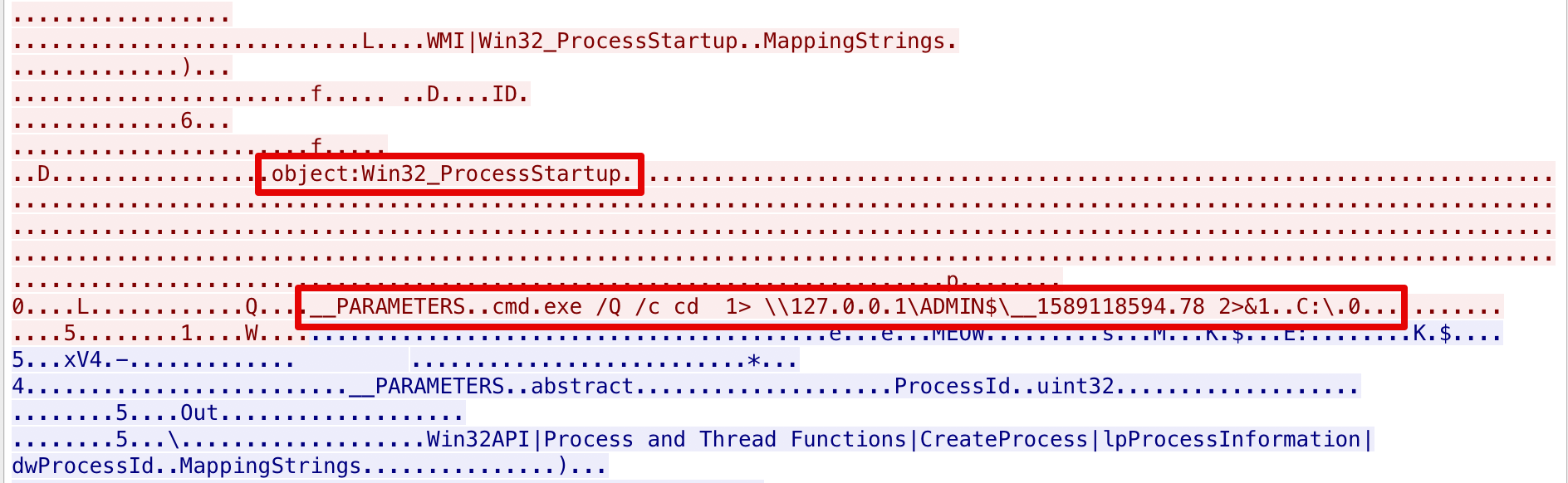

Hunting for this type of activity has a lot in common with the hunt we previously did for wmiexec.

For example, in terms of process creation the pattern will always be the same:

As it is possible to see, the command line arguments of cmd.exe use output redirection to ADMIN$ even in this case.

Another possible detection opportunity is given by the parent-child process anomaly of mmc.exe spawning cmd.exe. However this is true only when the -object MMC20 option is used within the tool, as shown below:

dcomexec.py -object MMC20 ISENGARD/Administrator:1qazxsw2..@172.16.119.140

Other DCOM meethods will result in different parent processes for cmd.exe, such as explorer.exe instead of mmc.

From the network side, we could apply the same logic we used before. The strings would clearly change, since the technique is different but we should be able to extract some kind of information anyways:

As we can see, the ExecuteShellCommand string was present in a TCP conversation. Now, ExecuteShellCommand is the method that is exposed by the MMC2.0 DCOM interface and therefore it could be a decent indicator of this activity. The same process could be repeated for every other execution mechanism that the tool provides.

Final Words

I’m not a SOC analyst and it is possible that I made some mistakes (very optimistic). The purpose of this post is not to flex hunting skills or so, just document attacks and how they might manifest within your environment.

Additionally, a lot of the “detections” that I presented can be quite easily bypassed by doing some minor tweaks in the scripts code. Impacket is a fantastic framework and the provided examples + comments would make such changes almost trivial ¯\_(ツ)_/¯